Este tópico está presentemente marcado como "adormecido"—a última mensagem tem mais de 90 dias. Pode acordar o tópico publicando uma resposta.

1baswood

A new year and a new thread. I read and reviewed only 50 books last year I hope to do better this year. Time is running out for me to read all the books I want to read before I die.

2baswood

Its good to have a project and there is no better time to think about next years reading than on New Years eve. I am discounting New Years day, because of a suspected hangover from the night before.

Three projects this year and here is my list of authors I hope to get through (only the highlights)

Tudor Literature:

Robert Greene:

the mirror of modeste

Gwydonius

Arbasto

Morando

Mamillia

Pandosto

Anthony Munday

Fidele and Fortunio

John Lyly

Campaspse

Sapho

Phao

George Peele

The Arraignement of Paris

Battle of Alcazar

The troublesome reign of King John

Famous chronicle of king Edward I

Thomas Kyd

The Spanish tragedy

Christopher Marlowe

Dido Queen of Carthage

Tamburlaine

The Jew of malta

Edward II

Doctor Faustus

Thomas Nashe

The anatomy of Absurdity

An almond for a Parrat

Thomas Lodge

Rosalynde

Edmund Spenser

Fairie Queen

William Shakespeare

The Comedy Of Errors

And so my project for the year is to get to the date of 1590 which was probably the date when Shakespeare wrote his first plays.

Unread Books From My Shelf (all authors with surnames starting with B) and so:

Saul Bellow

Balzac

Simone de Beauvoir

A S Byatt

Anthony Burgess

Malcolm Bradbury

John Buchan

Arnold Bennett

Pat Barker

Julian Barnes

Samuel Beckett

Djuna Barnes

Anthony Burgess

Science Fiction

Iain M Banks

Three projects this year and here is my list of authors I hope to get through (only the highlights)

Tudor Literature:

Robert Greene:

the mirror of modeste

Gwydonius

Arbasto

Morando

Mamillia

Pandosto

Anthony Munday

Fidele and Fortunio

John Lyly

Campaspse

Sapho

Phao

George Peele

The Arraignement of Paris

Battle of Alcazar

The troublesome reign of King John

Famous chronicle of king Edward I

Thomas Kyd

The Spanish tragedy

Christopher Marlowe

Dido Queen of Carthage

Tamburlaine

The Jew of malta

Edward II

Doctor Faustus

Thomas Nashe

The anatomy of Absurdity

An almond for a Parrat

Thomas Lodge

Rosalynde

Edmund Spenser

Fairie Queen

William Shakespeare

The Comedy Of Errors

And so my project for the year is to get to the date of 1590 which was probably the date when Shakespeare wrote his first plays.

Unread Books From My Shelf (all authors with surnames starting with B) and so:

Saul Bellow

Balzac

Simone de Beauvoir

A S Byatt

Anthony Burgess

Malcolm Bradbury

John Buchan

Arnold Bennett

Pat Barker

Julian Barnes

Samuel Beckett

Djuna Barnes

Anthony Burgess

Science Fiction

Iain M Banks

4baswood

Astrophil and Stella by Sir Philip Sidney

Professor Jonathan Smith has a blog where he analyses each of the 108 sonnets in Sidney’s collection of poems and in his introduction he compares them to Shakespeare’s sonnets.

“I like to say that a great sonnet is a small piece of art of great value, but available to anyone to own. Shakespeare might have more of his sonnets hanging in the Louvre or the Hermitage, but any collector would be proud to have a Sidney in her own collection.”

Sir Philip Sidney died at the age of 32 after wounds received in a skirmish at Zutphen (on the continent) in 1586. He had written his sonnet and song collection probably between 1581- 84 but they were not published during his lifetime, however they would have been read by a select group of admirers in manuscript form. Sidney was a courtier to queen Elizabeth I, member of Parliament, scholar, soldier and related to the Earl of Leicester who was a leading member of the protestant group at Court. All of his literary works were published after his death and it is these that have carried his fame through to current times as he had a fairly chequered career at Court, because Elizabeth kept the young man at arms length, perhaps suspicious of his connections in Europe.

A sonnet derived from an Italian word meaning little poem is recognised as having fourteen lines that follow a strict rhyming scheme and a specific structure. In Elizabethan times sonnets were typically poems of love based on the Italian writer Petrarchs (14th century) collection of songs and sonnets dedicated to his would be lover Laura. The English sonnet had been developed a couple of centuries later by Thomas Wyatt and the Earl of Surrey and in Sidney’s day were featured in collections by George Gascoigne and Thomas Watson, they became known as the poems of unrequited love. Sidney is now recognised among the great triumvirate of Elizabethan sonneteers, the others being Spenser and Shakespeare.

The object of Sidney’s passion is Stella and Astrophil is her star-lover. Sidney’s poems of unrequited love are based to some extent on personal experience. Stella has been identified as Penelope Devereux who Sidney first met in 1575 when she was fourteen years old. Sidney’s family had drawn up a contract of marriage for Sidney and Penelope, but unfortunately Penelope’s father died before the contract was signed and Penelope was contracted against her will to Lord Rich. There is little if anything specific in the poems (apart from some word play on Lord Rich’s name) to link them to Sidney’s love affair with Penelope, however knowing the history provides the reader with an interest in deciding how much of this comes straight from the heart of the poet. This is always tricky because of the formulaic nature of much courtier love poetry and Sidney’s poems do follow in that tradition; for example the life and death pains suffered by the male speaker/poet and the elevation of the lady into some kind of goddess.

Sonnet number 1

Loving in truth, and fain in verse my love to show,

That she (dear she) might take some pleasure of my pain,

Pleasure might cause her read, reading might make her know;

Knowledge might pity win, and pity grace obtain;

I sought fit words to paint the blackest face of woe,

Studying inventions fine, her wits to entertain;

Oft turning others’ leaves, to see if thence would flow

Some fresh and fruitful showers upon my sunburnt brain.

But words came halting forth, wanting Invention’s stay;

Invention, Nature’s child, fled step-dame Study’s blows;

And others’ feet still seemed but strangers in my way.

Thus great with child to speak, and helpless in my throes,

Biting my truant pen, beating myself for spite,

“Fool,” said my Muse to me, “look in thy heart, and write.”

In the very first sonnet Sidney addresses these issues. The first line states he is writing poems of his true love in verse and emphasises this point in the last line. He says that ‘oft turning other’s leaves’ is not good enough he is looking for ‘Invention’. It is for the reader to decide (if he/she wishes) how successful Sidney has been.

In my opinion Sidney does take his sonnet collection to another level from those that had preceded him. For a start most of the poems read well, there is very little awkwardness and when there is, it is usually for poetic effect. His poems are well structured with rhyming schemes that work well and with variations from the Italian formula that points to a more particular English sonnet style. He stresses in his first sonnet that Invention is key to his poetry making and while he does not always stray too far away from traditional courtier love poetry his poems have a level of invention that makes them consistently interesting. I read through these 108 sonnets always looking forward to reading the next one.

The sonnets seem to fit together, they seem to describe an actual love affair, however one sided it might be. We have to wait until sonnet 73 when he steals a kiss while Stella is asleep and this is possibly for the speaker the high point of the affair. It is sonnet 82 where he tries to have the last word on that stolen kiss, but now the writing is on the wall and Stella has become angry with him and it is a short step for her not wishing, or being prevented from seeing him again. Throughout the collection there is an ongoing debate about reason versus passion as the speaker struggles to contain himself. There are poems that personify certain feelings or sins, there are poems of serious reflection and there are poems based around small incidents. There are many poems about the beauty of Stella particularly the power emanating from her eyes. Much of this ground was covered in Petrarch’s Laura sonnets, but Sidney finds different, perhaps better, perhaps less artificial ways of dealing with themes that had become cliché.

There are many poems that can stand alone outside of the collection for example sonnet 78 that takes jealousy as its subject; warning in the final line that the beast of jealousy can lead the sufferer into wearing the horns of a cuckold.

O how the pleasant airs of true love be

Infected by those vapours which arise

From out that noisome gulf, which gaping lies

Between the jaws of hellish jealousy:

A monster, others’ harm, self-misery,

Beauty’s plague, virtue’s scourge, succour of lies;

Who his own joy to his own hurt applies,

And only cherish doth with injury;

Who since he hath, by nature’s special grace,

So piercing paws as spoil when they embrace,

So nimble feet, as stir still, though on thorns;

So many eyes aye seeking their own woe,

So ample ears, as never good news know:

Is it not ill that such a devil wants horns?

Astrophil and Stella has been one of the high points of my reading in Tudor literature. I suppose readers unaware of the cultural differences and not used to reading poetry might find many of these poems artificial and/or difficult, but for me they were a five star read.

Professor Jonathan Smith has a blog where he analyses each of the 108 sonnets in Sidney’s collection of poems and in his introduction he compares them to Shakespeare’s sonnets.

“I like to say that a great sonnet is a small piece of art of great value, but available to anyone to own. Shakespeare might have more of his sonnets hanging in the Louvre or the Hermitage, but any collector would be proud to have a Sidney in her own collection.”

Sir Philip Sidney died at the age of 32 after wounds received in a skirmish at Zutphen (on the continent) in 1586. He had written his sonnet and song collection probably between 1581- 84 but they were not published during his lifetime, however they would have been read by a select group of admirers in manuscript form. Sidney was a courtier to queen Elizabeth I, member of Parliament, scholar, soldier and related to the Earl of Leicester who was a leading member of the protestant group at Court. All of his literary works were published after his death and it is these that have carried his fame through to current times as he had a fairly chequered career at Court, because Elizabeth kept the young man at arms length, perhaps suspicious of his connections in Europe.

A sonnet derived from an Italian word meaning little poem is recognised as having fourteen lines that follow a strict rhyming scheme and a specific structure. In Elizabethan times sonnets were typically poems of love based on the Italian writer Petrarchs (14th century) collection of songs and sonnets dedicated to his would be lover Laura. The English sonnet had been developed a couple of centuries later by Thomas Wyatt and the Earl of Surrey and in Sidney’s day were featured in collections by George Gascoigne and Thomas Watson, they became known as the poems of unrequited love. Sidney is now recognised among the great triumvirate of Elizabethan sonneteers, the others being Spenser and Shakespeare.

The object of Sidney’s passion is Stella and Astrophil is her star-lover. Sidney’s poems of unrequited love are based to some extent on personal experience. Stella has been identified as Penelope Devereux who Sidney first met in 1575 when she was fourteen years old. Sidney’s family had drawn up a contract of marriage for Sidney and Penelope, but unfortunately Penelope’s father died before the contract was signed and Penelope was contracted against her will to Lord Rich. There is little if anything specific in the poems (apart from some word play on Lord Rich’s name) to link them to Sidney’s love affair with Penelope, however knowing the history provides the reader with an interest in deciding how much of this comes straight from the heart of the poet. This is always tricky because of the formulaic nature of much courtier love poetry and Sidney’s poems do follow in that tradition; for example the life and death pains suffered by the male speaker/poet and the elevation of the lady into some kind of goddess.

Sonnet number 1

Loving in truth, and fain in verse my love to show,

That she (dear she) might take some pleasure of my pain,

Pleasure might cause her read, reading might make her know;

Knowledge might pity win, and pity grace obtain;

I sought fit words to paint the blackest face of woe,

Studying inventions fine, her wits to entertain;

Oft turning others’ leaves, to see if thence would flow

Some fresh and fruitful showers upon my sunburnt brain.

But words came halting forth, wanting Invention’s stay;

Invention, Nature’s child, fled step-dame Study’s blows;

And others’ feet still seemed but strangers in my way.

Thus great with child to speak, and helpless in my throes,

Biting my truant pen, beating myself for spite,

“Fool,” said my Muse to me, “look in thy heart, and write.”

In the very first sonnet Sidney addresses these issues. The first line states he is writing poems of his true love in verse and emphasises this point in the last line. He says that ‘oft turning other’s leaves’ is not good enough he is looking for ‘Invention’. It is for the reader to decide (if he/she wishes) how successful Sidney has been.

In my opinion Sidney does take his sonnet collection to another level from those that had preceded him. For a start most of the poems read well, there is very little awkwardness and when there is, it is usually for poetic effect. His poems are well structured with rhyming schemes that work well and with variations from the Italian formula that points to a more particular English sonnet style. He stresses in his first sonnet that Invention is key to his poetry making and while he does not always stray too far away from traditional courtier love poetry his poems have a level of invention that makes them consistently interesting. I read through these 108 sonnets always looking forward to reading the next one.

The sonnets seem to fit together, they seem to describe an actual love affair, however one sided it might be. We have to wait until sonnet 73 when he steals a kiss while Stella is asleep and this is possibly for the speaker the high point of the affair. It is sonnet 82 where he tries to have the last word on that stolen kiss, but now the writing is on the wall and Stella has become angry with him and it is a short step for her not wishing, or being prevented from seeing him again. Throughout the collection there is an ongoing debate about reason versus passion as the speaker struggles to contain himself. There are poems that personify certain feelings or sins, there are poems of serious reflection and there are poems based around small incidents. There are many poems about the beauty of Stella particularly the power emanating from her eyes. Much of this ground was covered in Petrarch’s Laura sonnets, but Sidney finds different, perhaps better, perhaps less artificial ways of dealing with themes that had become cliché.

There are many poems that can stand alone outside of the collection for example sonnet 78 that takes jealousy as its subject; warning in the final line that the beast of jealousy can lead the sufferer into wearing the horns of a cuckold.

O how the pleasant airs of true love be

Infected by those vapours which arise

From out that noisome gulf, which gaping lies

Between the jaws of hellish jealousy:

A monster, others’ harm, self-misery,

Beauty’s plague, virtue’s scourge, succour of lies;

Who his own joy to his own hurt applies,

And only cherish doth with injury;

Who since he hath, by nature’s special grace,

So piercing paws as spoil when they embrace,

So nimble feet, as stir still, though on thorns;

So many eyes aye seeking their own woe,

So ample ears, as never good news know:

Is it not ill that such a devil wants horns?

Astrophil and Stella has been one of the high points of my reading in Tudor literature. I suppose readers unaware of the cultural differences and not used to reading poetry might find many of these poems artificial and/or difficult, but for me they were a five star read.

6tonikat

>4 baswood: happy new year. A lovely review to start the year. I've not read Sidney and am a bit wary after Shakespeares sonnets (I've done this backwards), of awkwardness (having read of Shakespeare's reactions to some extent), and a bit of Petrarch. So, you've encouraged me. I think I may have mentioned before that there was an album released a few years ago called My Lady Rich, and I think indeed it is the same Lady Rich, who has been linked to other literature too (an album of music from that time).

I love his final line in this lovely first sonnet. I'm grateful for your introduction.

I love his final line in this lovely first sonnet. I'm grateful for your introduction.

7dchaikin

An impactful 32 years, Sidney had. Great post to kick off your new thread. Appreciate the perspective on Petrarch and the English sonnet.

8thorold

Happy New Year!

>2 baswood: Looks as though you can’t go far wrong with those “writers beginning with B”!

Looking forward to having a proper look at what you say about Sidney and sonnets when I’m back on a big screen. Petrarch is moving steadily up my to-do list. (BTW: don’t let Sidney’s bad experience put you off Zutphen!)

>2 baswood: Looks as though you can’t go far wrong with those “writers beginning with B”!

Looking forward to having a proper look at what you say about Sidney and sonnets when I’m back on a big screen. Petrarch is moving steadily up my to-do list. (BTW: don’t let Sidney’s bad experience put you off Zutphen!)

10baswood

Leicester’s Commonwealth; The Copy of a letter Written by a Master of Art of Cambridge (1584) and related documents by Dwight Peck

Leicester’s Commonwealth is a scurrilous attack on Robert Dudley Earl of Leicestershire and favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. It was printed anonymously in France and found its way into Tudor England in large quantities, vigorous attempts were made to squash its promulgation and attempts were made to smoke out the authors and printers, but these were unsuccessful at the time. The book purported to tell the inside story (the black legend) of the Earl of Leicester and was taken as a valid source by historians and fictionalists: Sir Walter Scott did much to further the view that Leicester was a thoroughly bad lot. D C Peck’s edition of the Commonwealth puts the whole thing in context with an excellent introduction, extensive notes and summary of the latest historical research as at 1985 when his edition was printed.

The letter itself takes the form of a secret conversation between a Scholar and a Lawyer witnessed and written up by a Master of Art of Cambridge. The conversation starts innocently enough as the topic for discussion is the definition of a traitor, it is clear that the scholar is a protestant and his friend the lawyer is a catholic. They seem to agree that catholics in a protestant country could strictly be defined as traitors, but would not be traitors under law until they took action against the state in the name of their own religion. Many examples in Europe are given of protestants living peacefully in catholic countries and vice versa. The conversation then moves to consider the actions of the Earl of Leicester and very soon turns into a detailed indictment of the treachery and crimes he has committed, while serving as a courtier and close advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. The crimes mount and it feels like once they have started on the subject of the Earl then common sense seems to fly out the window it becomes a little hysterical. He is accused of murder, lechery, bigamy, rape, corruption, atheism and really anything else that they can think of. They conclude that he is the most powerful man in England and effectively runs the country for his own financial gain effectively making it Leicester’s commonwealth. They give as evidence many examples of his actions: the murders he has committed, the women he has spoiled. the extortions and corruption that constitute his working methods. They then turn to discuss his traitorous family and the history of the Dudleys.

The conversation calms down when they consider the huge issue of the succession to Elizabeth I. There is a history lesson of who has a claim to the throne and these are discussed in some detail, with agreement that King James of Scotland would make the best candidate. However they cannot stop talking about Leicester and the final part of the letter reiterates the crimes and the ambitions of the Earl:

He Killed his first wife Amy Robsart so that he could marry the queen

He killed the Earl of Sussex after an affair with his wife.

He committed bigamy with Lady Sheffield

He was responsible for the Drayton Basset riot where men were killed.

Peck’s view is that the Commonwealth was written by catholics in exile in France and that there were several contributors, this would account for the unevenness of the text. The allegations against Leicester can certainly not be proved, but that does not mean that they are entirely false. It is clear that Leicester was the queens favourite for a long time and as such wielded tremendous power at Court. He was a proud man and was a forceful enemy to the rival factions at court and it was easy to see why the attacks against him became personal. Peck says that the information in the Commonwealth cannot be relied upon for the facts of the case but they are a reliable guide to the “gossip’ of the time.

The Commonwealth is generally well written and there is some intentional humour, there are some parts that are not so interesting, but generally the text is a lively window into what was being talked about outside of the Queens court, something like a modern scandal sheet journal. Libellous it certainly was and dangerous for the authors and printers, well worth a read (its free on the internet) for readers interested in the Tudors. For me it was a four star read.

Leicester’s Commonwealth is a scurrilous attack on Robert Dudley Earl of Leicestershire and favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. It was printed anonymously in France and found its way into Tudor England in large quantities, vigorous attempts were made to squash its promulgation and attempts were made to smoke out the authors and printers, but these were unsuccessful at the time. The book purported to tell the inside story (the black legend) of the Earl of Leicester and was taken as a valid source by historians and fictionalists: Sir Walter Scott did much to further the view that Leicester was a thoroughly bad lot. D C Peck’s edition of the Commonwealth puts the whole thing in context with an excellent introduction, extensive notes and summary of the latest historical research as at 1985 when his edition was printed.

The letter itself takes the form of a secret conversation between a Scholar and a Lawyer witnessed and written up by a Master of Art of Cambridge. The conversation starts innocently enough as the topic for discussion is the definition of a traitor, it is clear that the scholar is a protestant and his friend the lawyer is a catholic. They seem to agree that catholics in a protestant country could strictly be defined as traitors, but would not be traitors under law until they took action against the state in the name of their own religion. Many examples in Europe are given of protestants living peacefully in catholic countries and vice versa. The conversation then moves to consider the actions of the Earl of Leicester and very soon turns into a detailed indictment of the treachery and crimes he has committed, while serving as a courtier and close advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. The crimes mount and it feels like once they have started on the subject of the Earl then common sense seems to fly out the window it becomes a little hysterical. He is accused of murder, lechery, bigamy, rape, corruption, atheism and really anything else that they can think of. They conclude that he is the most powerful man in England and effectively runs the country for his own financial gain effectively making it Leicester’s commonwealth. They give as evidence many examples of his actions: the murders he has committed, the women he has spoiled. the extortions and corruption that constitute his working methods. They then turn to discuss his traitorous family and the history of the Dudleys.

The conversation calms down when they consider the huge issue of the succession to Elizabeth I. There is a history lesson of who has a claim to the throne and these are discussed in some detail, with agreement that King James of Scotland would make the best candidate. However they cannot stop talking about Leicester and the final part of the letter reiterates the crimes and the ambitions of the Earl:

He Killed his first wife Amy Robsart so that he could marry the queen

He killed the Earl of Sussex after an affair with his wife.

He committed bigamy with Lady Sheffield

He was responsible for the Drayton Basset riot where men were killed.

Peck’s view is that the Commonwealth was written by catholics in exile in France and that there were several contributors, this would account for the unevenness of the text. The allegations against Leicester can certainly not be proved, but that does not mean that they are entirely false. It is clear that Leicester was the queens favourite for a long time and as such wielded tremendous power at Court. He was a proud man and was a forceful enemy to the rival factions at court and it was easy to see why the attacks against him became personal. Peck says that the information in the Commonwealth cannot be relied upon for the facts of the case but they are a reliable guide to the “gossip’ of the time.

The Commonwealth is generally well written and there is some intentional humour, there are some parts that are not so interesting, but generally the text is a lively window into what was being talked about outside of the Queens court, something like a modern scandal sheet journal. Libellous it certainly was and dangerous for the authors and printers, well worth a read (its free on the internet) for readers interested in the Tudors. For me it was a four star read.

12AnnieMod

>10 baswood: That's a book I have a hate/love relationship with - and this is before I had even read it. Leicester was one of the reasons I got interested in the Tudors to start with (him and Jane Grey) - so I had read (or at least skimmed) most of what had been written about him through the centuries - at least the books that can be had for a reasonable price. And yet, that book just sits there and just stares at me... I've read essays about it, I've seen it mentioned in numerous other books and still...

13dukedom_enough

>2 baswood: What will the first Ian M. Banks book be?

14baswood

>13 dukedom_enough: I have the first three books in the Culture series and so I will start with Consider Phlebas

But my first "science fiction" book this year is which I am reading at the moment is The Temple of Nature; or the origin of Society by Erasmus Darwin published in 1802

But my first "science fiction" book this year is which I am reading at the moment is The Temple of Nature; or the origin of Society by Erasmus Darwin published in 1802

15rhian_of_oz

>14 baswood: Do you plan on reading The Wasp Factory? I'll be very interested in seeing your thoughts if so.

16baswood

>15 rhian_of_oz: I have read The Wasp Factory but that was a long time before I started writing my reviews of what I have read. I can't remember too much about it, but I have enjoyed all the Ian Bank's novels I have read.

17baswood

The Temple of Nature, or the Origin of Society

Erasmus Darwin was an English Physician, natural philosopher, physiologist, inventor and slave-trade abolitionist; he died in 1802 and his long poem The Temple of Nature was published after his death. He was the grandfather of Charles Darwin and had enjoyed popular success with The Botanic Garden another long poem published in 1791. According to the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction he is now considered an important figure in the genre of proto Science fiction because of his theories on evolution.

The book is described as a poem, with philosophical notes, the actual poem consists of nearly a thousand rhyming couplets in iambic pentameter with footnotes explaining or surmising about the scientific theories therein. There are also extensive notes following the poem, but I was far too tired to go into these having read the poem in a single sitting. Darwin’s The Botanic garden had enjoyed critical as well as popular success, but probably The temple of Nature was one poem too many. He had been seen as a forerunner to the romantic poets and there are many passages similar to this in his poem:

"Now young DESIRES, on purple pinions borne,

Mount the warm gales of Manhood's rising morn;

With softer fires through virgin bosoms dart,

Flush the pale cheek, and goad the tender heart.

Ere the weak powers of transient Life decay,

And Heaven's ethereal image melts away;

LOVE with nice touch renews the organic frame,

Forms a young Ens, another and the same;

Gives from his rosy lips the vital breath,

And parries with his hand the shafts of death;

While BEAUTY broods with angel wings unfurl'd

O'er nascent life, and saves the sinking world.

However it does sound much too artificial, he was not interested in describing feelings or the inner workings of the mind. His use of the poetic form was to bring attention to his scientific and anthropological theories. His didactic style wears thin and his attempts to intersperse this with classical mythology only serves to produce more footnotes for the confused reader. Darwin says in his introduction that his poem is not meant to instruct its aim is simply to amuse by bringing distinctly to the imagination, the beautiful and sublime images of the operations of nature. It is his theories on the operation of nature that are of interest because he tells us that life began beneath the sea, with atoms and chemical reactions producing cellular creatures that evolved into the life forms that we see today. He must have realised that these ideas on evolution might be rejected by the religious community because he kind of shoe horns in the Adam and Eve story from the bible.

The poem might be interesting for readers who are researching into early ideas on evolution, or for those that like the “romantic” language of Darwin’s rhyming couplets. Apart from a few arresting passages, I was glad to be finished with it and so 2.5 stars.

18dchaikin

Kudos for getting through it. He was clearly an important influence on Charles and is interesting to read about, but maybe not so pleasant to actually read.

21baswood

The Discoverie Of Witchcraft - Reginald Scot

After just having read Philip Sidney’s Astrophel and Stella; a collection of love poetry written by a courtier to Queen Elizabeth, with its carefully chosen imagery and language that would appeal to the higher echelons of society, it was like taking a cold shower to read Scots book, which delves into the underbelly of Tudor England. Scots book was certainly not aimed at common people many of whom could not read, but it was aimed at the class of people that would have dealings with them, either professionally or through religion.

Reginald Scot published his discoverie of witchcraft in 1584. It was a book that purported to be against the practice of witches, but comes perilously close to being a textbook of witch-craft. Cornelius Agrippa had published his Occult Philosophy: Natural Magic some fifty years earlier, in which he had written details of arcane practices that he thought provided clues to the mysteries of life. Reginald Scot writes in similar detail with many additions from other works, but says that these are fables, old wives tales or complete rubbish written to influence gullible people. Scot was writing at the start of a phase of renewed persecutions against witches or wise women and it is clear in his view that the renewed drive against poor, simple, mostly elderly women was a campaign against some of the most vulnerable people in society.

Scot claims that his book is written to celebrate the glory and power of God, because all of the wonderful, dangerous, magical powers that witches are claimed to posses could not possibly exist because such powers can only be used and known by God. The power of God as detailed in the bible is the only supernatural power there is and it does not need the foolish ‘trumperie’ of magical charms, spells, and other paraphernalia that is associated with witches. Scot was a protestant reformer and he delights in equating the practices of witchcraft with the practices of the catholic church. He sees no difference between the two and goes on to say that the catholic church’s use of relics, and the mysticism of its services is similar to witchcraft in that it relies on the ignorance and naivety of people for its success.

The majority of Scots book is a recycling of, or translations from other sources. Particularly Jean Bodin’s Daemonomania and Malleus Maleficarum by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Springer; he also uses many stories and examples from the Bible as well as classical literature. His method of working is to transcribe these items in some detail and then to dismiss them as nonsense or absurd or attempts to usurp the power of God. There are 26 volumes amounting to over 600 pages of modern text for those people who like to dwell in such matters, most of the time I skimmed, looking for relevance to life in Tudor England. Scot only gives a few examples of witchcraft practised in England, but there are more examples of stories from the continent.

The book covers: the power of witches; spells, transformations, charms, with a section that warns readers who are loathe to read bawdy or filthy stories to skip over that part. It covers the Cabala and the power words used by the Jews, it covers miracles and oracles, alchemy, conjuration, powers of the angels devils and spirits, and a long section on magic tricks and how they work. It ends with a strong refutation of most of what has gone before.

I suppose because the book is full of superstitions, of knavery, sharp practices and spiritualistic manifestations and it was extremely popular in Tudor England is comment enough on the society at that time. King James later ordered copies of the book to be burnt, but that was because of its fierce anti-catholic stance and his own belief that witchcraft was a problem in early seventeenth century England. A book to dip into perhaps, but most of it sounds preposterous to me and I think it will for the majority of readers today 2.5 stars.

After just having read Philip Sidney’s Astrophel and Stella; a collection of love poetry written by a courtier to Queen Elizabeth, with its carefully chosen imagery and language that would appeal to the higher echelons of society, it was like taking a cold shower to read Scots book, which delves into the underbelly of Tudor England. Scots book was certainly not aimed at common people many of whom could not read, but it was aimed at the class of people that would have dealings with them, either professionally or through religion.

Reginald Scot published his discoverie of witchcraft in 1584. It was a book that purported to be against the practice of witches, but comes perilously close to being a textbook of witch-craft. Cornelius Agrippa had published his Occult Philosophy: Natural Magic some fifty years earlier, in which he had written details of arcane practices that he thought provided clues to the mysteries of life. Reginald Scot writes in similar detail with many additions from other works, but says that these are fables, old wives tales or complete rubbish written to influence gullible people. Scot was writing at the start of a phase of renewed persecutions against witches or wise women and it is clear in his view that the renewed drive against poor, simple, mostly elderly women was a campaign against some of the most vulnerable people in society.

Scot claims that his book is written to celebrate the glory and power of God, because all of the wonderful, dangerous, magical powers that witches are claimed to posses could not possibly exist because such powers can only be used and known by God. The power of God as detailed in the bible is the only supernatural power there is and it does not need the foolish ‘trumperie’ of magical charms, spells, and other paraphernalia that is associated with witches. Scot was a protestant reformer and he delights in equating the practices of witchcraft with the practices of the catholic church. He sees no difference between the two and goes on to say that the catholic church’s use of relics, and the mysticism of its services is similar to witchcraft in that it relies on the ignorance and naivety of people for its success.

The majority of Scots book is a recycling of, or translations from other sources. Particularly Jean Bodin’s Daemonomania and Malleus Maleficarum by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Springer; he also uses many stories and examples from the Bible as well as classical literature. His method of working is to transcribe these items in some detail and then to dismiss them as nonsense or absurd or attempts to usurp the power of God. There are 26 volumes amounting to over 600 pages of modern text for those people who like to dwell in such matters, most of the time I skimmed, looking for relevance to life in Tudor England. Scot only gives a few examples of witchcraft practised in England, but there are more examples of stories from the continent.

The book covers: the power of witches; spells, transformations, charms, with a section that warns readers who are loathe to read bawdy or filthy stories to skip over that part. It covers the Cabala and the power words used by the Jews, it covers miracles and oracles, alchemy, conjuration, powers of the angels devils and spirits, and a long section on magic tricks and how they work. It ends with a strong refutation of most of what has gone before.

I suppose because the book is full of superstitions, of knavery, sharp practices and spiritualistic manifestations and it was extremely popular in Tudor England is comment enough on the society at that time. King James later ordered copies of the book to be burnt, but that was because of its fierce anti-catholic stance and his own belief that witchcraft was a problem in early seventeenth century England. A book to dip into perhaps, but most of it sounds preposterous to me and I think it will for the majority of readers today 2.5 stars.

22SassyLassy

Happy to have found your new thread - there's so much here already.

>2 baswood: Those Bs make a wonderful collection. Do you start browsing in book stores at letter A? I did this for a while and soon realized I rarely made it beyond C before my budget ran out, so now I randomly choose a starting letter.

>10 baswood: Leicester continues to fascinate so many people on so many levels. Scott may not have had him right, but Kenilworth was certainly fun.

>21 baswood: This sounds like a dangerous book to have owned in its time.

>2 baswood: Those Bs make a wonderful collection. Do you start browsing in book stores at letter A? I did this for a while and soon realized I rarely made it beyond C before my budget ran out, so now I randomly choose a starting letter.

>10 baswood: Leicester continues to fascinate so many people on so many levels. Scott may not have had him right, but Kenilworth was certainly fun.

>21 baswood: This sounds like a dangerous book to have owned in its time.

23baswood

>22 SassyLassy: Strangely enough if a bookshop has arranged its books alphabetically the thats the way I will browse, if I have not got a specific author in mind.

I have still one book to read from the A list and that is A history of God by Karen Armstrong. This is not a book that I would have browsed in a bookshop, any mention of the God word in the title usually makes me pass over fairly quickly. The Karen Armstrong book was thrust into my hands by someone at our final book club meeting with the dreaded command "you must read this"

I have still one book to read from the A list and that is A history of God by Karen Armstrong. This is not a book that I would have browsed in a bookshop, any mention of the God word in the title usually makes me pass over fairly quickly. The Karen Armstrong book was thrust into my hands by someone at our final book club meeting with the dreaded command "you must read this"

24valkyrdeath

>21 baswood: Very interesting to read about The Discoverie of Witchcraft. As an amateur magician for the majority of my life it's a book I've read about many times but mostly in the context of it being the first ever published material explaining magic tricks, but I've never really thought about the work as a whole.

25dchaikin

>23 baswood: oh boy, hope you like Armstrong. I read one of her big books and basically concluded it was not worth all the time I had put into it.

>23 baswood: this is fun history. And nice of Scott to highlight the bawdy parts. I love that he uses the power and glory of god to reveal all this trickery is not supernatural, making it essentially a logical circle going nowhere. But it seems he had the right idea about the nature of witches.

>24 valkyrdeath: interesting about its reputation in magic.

>23 baswood: this is fun history. And nice of Scott to highlight the bawdy parts. I love that he uses the power and glory of god to reveal all this trickery is not supernatural, making it essentially a logical circle going nowhere. But it seems he had the right idea about the nature of witches.

>24 valkyrdeath: interesting about its reputation in magic.

26baswood

A History of God by Karen Armstrong

‘Human beings cannot endure emptiness and desolation: they will fill the vacuum by creating a new focus of meaning. The idols of fundamentalism are not good substitutes for God; if we are to create a vibrant new faith for the twenty-first century, we should, perhaps, ponder the history of God for somer lessons and warnings’

And so ends Karen Armstrong’s A History of God; the final chapter was entitled ‘Has God a future’ and for believers in God this will not sound a very optimistic note. A.N Wilson has been quoted as saying that this book is the most fascinating and learned survey of the biggest wild-goose chase in history - the quest for God. The History of God according to Armstrong seems to have been an attempt to know the unknowable.

Before her final two chapters which are both questions (The Death of God? and Has God a Future?) Armstrong takes the reader through the history of three monotheist religions; Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, she does this in some detail concerning herself with the history of religious thought, the sacred texts as they were received and the prominent men (nearly all men) who were the prophets, scholars and writers. Judaism being the oldest religion is given precedence in the early part of the book, but it gives the reader the background for christianity and then Islam. I found this early history interesting, but perhaps with too much detail, it took the emergence of Islam for the book to grab my intention. The history of the three religions is then brought up to date with chapters on philosophical thought, mysticism, attempts at reform and then finally the enlightenment.

The book has a glossary, notes, suggestions for further reading and a pretty good index and so it could make a decent reference book and I will keep it on my bookshelf to serve this purpose. All in all a bit too much history for me to enjoy the book as a read through experience, but it was the next book on my shelf to read. 3.5 stars.

27Nickelini

>26 baswood: I've read a few Karen Armstrong books and have since filed her as an author I wanted to like but don't. Sounds like I need to go to the library and read the last two chapters though.

28dchaikin

Bas - why, as I read that review of Armstrong, did I think to myself better you than me... I know, very rude and unfair thing to share. It does actually sound like it was worth reading.

29baswood

Fidele and Fortunio by Anthony Munday

Three Ladies of London - Anonymous.

Two plays from 1584/5 which Shakespeare might have seen when he first came to London in the mid 1580’s. Fidele and Fortunio as presented by Munday looks forward to the great drama that was to come at the end of the 16th century while Three ladies of London looks back towards an earlier era of morality plays. Both plays were popular enough to go into print and both have survived through the intervening centuries. I read them back to back on a misty, rainy afternoon in the French winter countryside and they lightened the gloom.

Anthony Munday (1560-1633) had a long career as a playwright, novelist, translator, entertainments for Lord Mayors shows, pamphleteer and spy. He was a man who seemed to have lived by his pen in what could be described as the popular media. He could certainly put words together and over 200 works have been attributed to him, but critical opinion says he was no poet. Fidele and Fortunato was registered in 1585 and described as a translation, which is probably why it has been attributed solely to Munday at a time when many plays for the London playhouses were collaborations. Munday’s play was more like a construction or interpretation from ‘Il Fedele’ which was an Italian Renaissance comedy by the Venetian playwright Pasqualigo.

For the London Stage Munday made some significant alterations. He excluded many of the minor characters adapting the plot to fit the reduced number of players. He removed much of the misogyny which was a feature of Italian comedy at the time and developed the characters a little better, while maintaining the touch of a light frothy comedy. The skeleton of the plot remains close to the original with its intrigues, star crossed lovers, magic charms, disguises and misunderstandings and it is set in Italy. It also has a standard funny character in the blustering, self important, but ultimately stupid Captain Crackstone. The play starts with the sad faced Fidele returning from the wars wanting to marry the woman he loves Victoria, however Fortunio has also fallen in love and in Fidele’s absence has been wooing Victoria for himself. Fortunio fearing Fidele’s return enlists the help of Captain Crackstone, but Crackstone hatches a plot to discredit Victoria with Fidele and Fortunio so that he can have her for himself. Victoria loves Fortunio and she hires the sorceress Medusa to use her magic, meanwhile Fidele asks his old schoolmaster Pedante for his help and he promptly falls in love with Victoria’s maid. Fortunio is fooled by Pedante in disguise and turns his attentions to Virginia who is in love with Fidele. The climax of the play is when Crackstone overplays his hand and ends up caught in a net by the city guards while he is disguised as Pedante. It all ends happily with the lovers getting the partners of their choosing.

The action has been speeded up from the original by Munday and there is hardly a dull moment with some witty dialogue and asides to the audience.

This is one of Crackstones asides to the audience when he is disguised as Pedante the schoolmaster; it is amusing as well as serving to move the plot along:

Crack-stone.

Softe, for it is night, I must not make any noyse I trowe:

Me thinks this apparell makes me learnd,

which of all these Starres doo I knowe.

Yonder is the gréen Dog, and the blew Beare,

Harry Horners Girdle, and the Lyons eare.Me thinkes I should spowt Lattin before I beware,

Argus mecum insputare?

Cur Canis tollit poplitem,

Cum mingit in parietem?

Alice tittle tattle Mistres Victoriaes Maid:

If I speake like the Schoolmaister, shée will neuer be afraid.

As soon as she opens the doore to let mée in:

With my Ropericall aliquanci I will begin.

Swinum, Velum, Porcum. Graye-goosorum iostibus:

Enter Fede¦le and Pe∣dante.

Rentibus dentibus, lofadishibus, come after vs.

I haue berayed my selfe I think with speaking so high:

This is Sir Fedele that is so nigh.

Till he be past it were not good for mée to appéere:

Therfore Ile slip into the Temple, and hide me in the Tombe that standeth héere.

Of course the scene ends with Crackstone rising from the tomb in which he has been hiding and frightening everyone to death.

The Three ladies was entered into the registry by author unknown in 1585 and it has the trappings of a morality play, while ignoring any religious connotations. The three ladies in question are. Fame, Love and Conscience and they are all in pursuit of Lucre. The characters of Dissimilation and Simplicity do battle with Fraud and Userie. Mercadore an Italian merchant arrives and he speaks in Pidgin English, he attempts to use Fraud and Userie to gain Lucre as do a Lawyer and an Artificier. Hospitality a dry old man appears on the scene and he is promptly murdered by Userie and so it goes on……….. The plot is threadbare to say the least and serves to highlight the dangers of Fraud, Userie and the pursuit of Lucre, There are no real characters and while some of the dialogue is fairly well written and probably was written to amuse as well as instruct the audience, it feels heavy and leaden beside Fidele and Fortunio.

The two plays serve to show the variety and development of drama in late Tudor England and paved the way for the explosion of talented playwrights who were just round the corner. While reading the plays it is interesting to imagine them being performed on stage and while Fidele and Fortunio would provide some entertainment, I cannot see how Three Ladies of London would be made to work and so I rate Fidele and Fortunio as 3 stars and Three Ladies of London as 2 stars.

30dchaikin

Google translate returned some interesting interpretations on Crackstone’s Latin. Fidele and Fortunion sounds like great fun. Enjoyed this whole post, especially with Shakespeare in mind.

31baswood

The Other Side of the Sun, Paul Capon

British Science fiction from the 1950’s; The other side of the sun was published in 1950 and was the first part of Capon’s Antigeos trilogy. The Golden age of science fiction perhaps, but in Capon’s hands it had not developed much beyond the stories of H G Wells some 50 years earlier. The discovery of a new planet on the same orbit as the earth around the sun, but largely hidden from the earth by the sun causes a sensation in the press. A space ship (rocket) is built in England and six people travel to the new planet named Antigeos. The crew are two scientists, an engineer and two passengers who have paid for their passage by donating funds for the expedition. The scientist daughter smuggles herself aboard with the help of one of the passengers and a romance develops. The spaceship lands on Antigeos which is populated by human-like creatures who have developed a more innocent, utopian-like society.

This is story telling that would certainly have appealed to me as a young teenager and I quite enjoyed it today, revelling in its innocence and sense of 1950’s unsophisticatedness. The depiction of 1950’s England feels nostalgic and uncomplicated and the journey to Antigeos is made without too much of a problem. The discovery of a new world and a different society is handled with a charming simplicity. there are tensions, but these are easily overcome and the sense of wonder keeps the pages turning. The story avoids the misogyny of much of the genre and skirts around any violent complications. A three star read.

32dchaikin

So maybe I’ve learned a few things through your reviews. The set up to this novel, a planet merely hidden by the sun and it’s utopian sounds a lot like the impossible physics of the early utopian novels you have reviewed here in CR.

33mabith

The Other Side of the Sun does sound a fun little lark, and nice to read some 50s SFF that's not smothered in misogyny or war.

34lisapeet

>31 baswood: And the cover is fabulous. Is that Freas or a look-alike?

35dukedom_enough

>31 baswood: The only Capon book I have read is Lost: A Moon. Somehow it seems odd to learn that he wrote anything else.

36baswood

Elizabeth: The Forgotten years by John Guy

The forgotten years according to John Guy are from 1584 until the Tudor Queen’s death in 1603. He claims that during these years Elizabeth’s reputation as Good Queen Bess was cemented by the opinion makers, after all she repelled the Spanish Armadas and kept England at peace during this period. Guy says he wants to get closer to the truth about the ageing Elizabeth and so makes his book both a history and a character study of the Queen. He puts some popular beliefs to bed, especially those promulgated by the Tudor propagandists and their Victorian followers by looking more closely at Elizabeth’s letters and other original documents from the period: some of which have come to light only in more recent times. Elizabeth emerges as an avaricious, spiteful, proud, vain, autocratic woman who only thought of the welfare of her country in conjunction with her own prosperity, but of course she was hardly any different from the men and women who surrounded her at court. She overcame her personal vulnerability and fear to rule very much as she saw fit and compared with her predecessors Queen Mary and Henry VIII, then she was certainly no worse then them. She ruled for 44 years in a man’s world keeping her country united and free from invasions, which was an achievement in itself and despite not having an heir to the throne, anarchy and civil war were avoided at her death.

Guy writes his history largely chronologically after having provided a brief introduction to the early part of Elizabeth’s reign. His writing style although rich in detail would appeal to the more casual reader; his explanations are clear and he provides additional detail where necessary and his use of letters and other personal documents provide the reader with a chance to see more rounded characters. Not only does he leave us with a vivid impression of the elderly queen, but also Robert Devereux the earl of Essex, William Cecil, and Francis Walsingham emerge from the shadows. He is able to give his readers an impression of how Elizabeth ran her government with some idea of the day to day workings of her court.

Although this is mainly a political/biographical history, there are snapshots of social conditions as they affected the politics for example the soldiers returning to England from the continent, who Elizabeth refused to pay; they formed gangs and social disturbances that needed to be controlled to prevent insurrections. There is also references to the theatres of London none more so than when players and playmakers at the Globe theatre were suspected of aiding and abetting the Earl of Essex when he challenged Elizabeth and her government (Essex was executed for treason).

In my opinion this is a lively and good historical account of the last Tudor government and its ageing Queen and it leaves me with the impression that I probably do not need to read another one and so a four star book.

The forgotten years according to John Guy are from 1584 until the Tudor Queen’s death in 1603. He claims that during these years Elizabeth’s reputation as Good Queen Bess was cemented by the opinion makers, after all she repelled the Spanish Armadas and kept England at peace during this period. Guy says he wants to get closer to the truth about the ageing Elizabeth and so makes his book both a history and a character study of the Queen. He puts some popular beliefs to bed, especially those promulgated by the Tudor propagandists and their Victorian followers by looking more closely at Elizabeth’s letters and other original documents from the period: some of which have come to light only in more recent times. Elizabeth emerges as an avaricious, spiteful, proud, vain, autocratic woman who only thought of the welfare of her country in conjunction with her own prosperity, but of course she was hardly any different from the men and women who surrounded her at court. She overcame her personal vulnerability and fear to rule very much as she saw fit and compared with her predecessors Queen Mary and Henry VIII, then she was certainly no worse then them. She ruled for 44 years in a man’s world keeping her country united and free from invasions, which was an achievement in itself and despite not having an heir to the throne, anarchy and civil war were avoided at her death.

Guy writes his history largely chronologically after having provided a brief introduction to the early part of Elizabeth’s reign. His writing style although rich in detail would appeal to the more casual reader; his explanations are clear and he provides additional detail where necessary and his use of letters and other personal documents provide the reader with a chance to see more rounded characters. Not only does he leave us with a vivid impression of the elderly queen, but also Robert Devereux the earl of Essex, William Cecil, and Francis Walsingham emerge from the shadows. He is able to give his readers an impression of how Elizabeth ran her government with some idea of the day to day workings of her court.

Although this is mainly a political/biographical history, there are snapshots of social conditions as they affected the politics for example the soldiers returning to England from the continent, who Elizabeth refused to pay; they formed gangs and social disturbances that needed to be controlled to prevent insurrections. There is also references to the theatres of London none more so than when players and playmakers at the Globe theatre were suspected of aiding and abetting the Earl of Essex when he challenged Elizabeth and her government (Essex was executed for treason).

In my opinion this is a lively and good historical account of the last Tudor government and its ageing Queen and it leaves me with the impression that I probably do not need to read another one and so a four star book.

37dchaikin

>37 dchaikin: Sounds terrific. Any surprises? “avaricious, spiteful, proud, vain, autocratic” is not exactly how I have imagined her. That line alone has me curious.

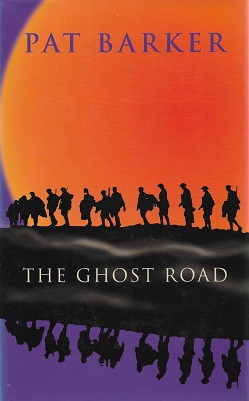

38baswood

The Eye in the Door by Pat Barker

“The epicritic grounded in the protopathic, the ultimate expression of the unity we persist in regarding as the condition of perfect health”

This is what Dr W.H.R Rivers (or perhaps Pat Barker) thinks as he struggles to help soldiers suffering from the effects of war in the trenches during the first world war. For a book that has a psychologist, neurologist, psychiatrist as its hero Barker does well in explaining the issues without the use of too much jargon and that is possibly why the extract above stood out from the text for me, because it is unrepresentative.

Barkers “The Eye in the Door” is an historical novel detailing the treatment of mentally wounded soldiers by Dr Rivers; one of whose tasks is to decide whether they are fit to return to active service. The time period is towards the end of the war when mental health issues were becoming more prevalent although little understood by many in the medical profession. While Doctor Rivers’ star patient Siegfried Sassoon is well documented the two major protagonist/patients; Billy Prior and Charles Manning are inventions by the author. The backdrop to the story are two major events of the period; an attempt to assassinate Lloyd George and the sensationalist headlines concerning a list of 47,000 people who because of their beliefs, race or sexual orientation were branded as undermining the British war effort. Prior and Manning’s invented stories interweave around the historical events in a way that is thoroughly convincing. In fact Barker’s depiction of an England that is suspicious, bureaucratic, nasty, class ridden, but jingoistic and fully committed to winning the war is distinctly plausible. It is a place where spies, intelligence and counter intelligence can destroy lives both innocent or guilty or more usually because they are seen to be different. Nasty grubby little people can flourish while across the channel the horrors of war still seem to be far enough away. Barker talks about bombing raids over London as though they were usual, but I think they were few and far between, it is the wounded soldiers and those home on leave that bring the war to England’s shores.

The novel is anti-war in so far as it describes in striking detail and imagery the horrors of trench warfare, but this contrasts with life in England where it is only citizens actions and thoughts about themselves and one another that cause problems. Soldiers experiencing a life at war as part of the war machine and then life at home amongst people who have no experience of the horrors, find themselves in two worlds and so it is unsurprising that people like Dr Rivers have to try put people back together again. It is a subject that provides fertile ground for novelists, but at the end of the day I am not convinced by ‘The Eye in the Door’. First of all it is all over far too quickly, Barker could have explored her characters further. I understand that those people who are well documented as part of the history of the times present limitations for the author, but even Manning and Prior her own characters hardly leap off the page and Dr Rivers is almost a cypher. Secondly I find her writing style curiously flat, I found there was nothing much on which to dwell and I ended up reading through it too quickly. There does not seem to be much of a plot, nothing appears resolved and I finished the book much as I started. These observations are personal to me as other readers might enjoy Barker’s writing style and as it is part of a trilogy of books then issues might feel more resolved in the final book. I have the third part of the trilogy sitting on my shelf waiting to be read, but I can’t say I am really looking forward to it and so a niggardly three stars from me.

39baswood

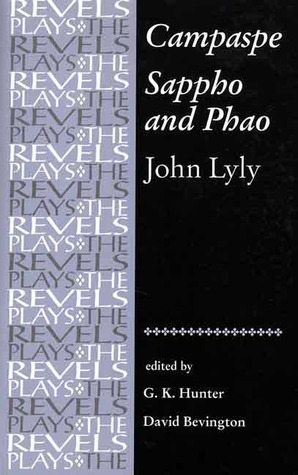

John Lyly - Campaspe, Sappho and Phao

Two plays published in 1584 and both performed at Whitehall in the presence of Queen Elizabeth I. Campaspe was reprinted in 1591, but there are no records of any other performances at this time. The plays have rarely been performed since, although very recently 2017 and 2018 there were productions of Sappho and Phao. It is not difficult to see why they have remained relatively obscure, because there is very little narrative drama, hardly any action and their merits are the intricate word play of Lyly and their topicality to courtiers of Elizabeth I. The plays although performed at Blackfriars theatre as well as at Whitehall were designed and written for Elizabeth’s court and they have not travelled very well since then. In my opinion there is as much pleasure to be had from reading the text as to seeing a production on stage (if you were able to find one).

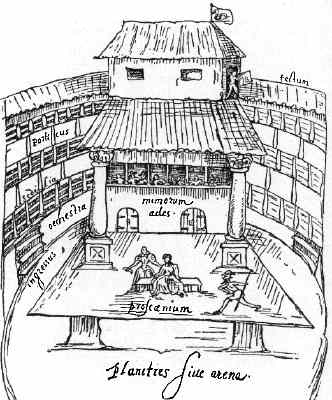

These are Lyly’s first two plays and both are original plays which have been developed from classical sources. They are written in prose form with a few songs interspersed. There are very few props needed perhaps a barrel on the stage for Campaspe and a bed for Sappho and Phao, they could be performed on a flat open space with a couple of spaces for entrances and exits. The players in Tudor times were boy actors and the audience would be seated around a rectangular hall perhaps on raised benches. Elizabeth I would have pride of place probably on a raised throne in front of the acting space. The plays were designed to appeal to a sophisticated courtly audience with a knowledge of classical literature, rhetoric and a veneration for humanistic ideals. In his prologue to a performance at Blackfriars Lyly makes it clear that his plays were not anything like the Italian renaissance comedies that were adapted by playwrights like Anthony Munday:

“Our intent was at this time to move inward delight, not outward lightness, and to breed (if it might be) soft smiling, not loud laughing knowing it to the wise to be as great pleasure to hear counsel mixed with wit as to the foolish to have sport mingled with rudeness. They were banished the theatre at Athens, and from Rome hissed, that brought parasites on the stage with apish actions, or fools with uncivil habits, or courtesans with immodist words. We have endeavoured to be as far from unseemly speeches to make your ears glow as we hope you will be from unkind reports to make our cheeks blush”

The inspiration for Campaspe comes from Plutarch’s Life of Alexander. The play opens with prisoners from the war with Thebes being presented to Alexander and two in particular the noble woman Timoclea and the lowly born but beautiful Campaspe are singled out for protection by Alexander. He falls in love with Campaspe and takes her to Apelles the most renowned painter of his generation to have a portrait made. Apelles falls in love with Campaspe and she in love with him and the issue for them both is what action Alexander will take if they dare to confess their love. Meanwhile Alexander is preparing to march into Persia in his bid to conquer the world. Alexander consults with some leading philosophers including Plato and Aristotle and the stoic Diogenes who lives in a barrel and has no respect for a soldier like Alexander. The topics of the play are of course love, particularly between high born and low born characters, morality, kingship, mercy and magnanimity and freedom. Lyly explores these ideas in his own inimitable way from many sides, sometimes in the same sentence, but his central idea is a comparison of Alexander the Great with Queen Elizabeth I.

The source for Sappho and Phao is Ovid’s Heroides, but Lily changes things around; Sappho is a queen (not a poetess) and Phao is a ferryman. The Goddess Venus makes Phao into the most desirable of men and with Cupid’s help she makes Sappho fall in love with him. Phao turns to Sibylla for advice and she warns him against being too proud. However Phao is so magnificent that Venus herself falls in love with him and she has to turn to her old lover Vulcan to make new arrows of disdain for Cupid to fire into Sappho and herself to jolt them out of love for Phao. There is also a cast of courtiers and servants to Sappho to discuss and debate issues similar to those of Campaspe. Themes concerning the behaviour of courtiers and court verses university are explored, however in this play Elizabeth I is more readily identified with Sappho and the major topic of the play is the struggle between carnal love and the need to maintain virtue. In Elizabeth’s case she was still considering the possibility of a marriage. In this play the affects of love on the central characters is explored by Lily by some witty and poignant dialogue. In both plays there are no subplots other characters are used to focus on the issues surrounding the love affairs.

Both these plays could be described as comedies (there is certainly no hint of tragedy) and they can be enjoyed as such because of the wit and word-play of John Lyly. Word-play in Lyly is highly antithetical and it gives his characters in these two plays the opportunity to explore the inherent contradictions in the human condition. His wit can certainly raise a smile and his similes and imagery can be both clever and arresting, if sometimes they need a bit of work to understand them. Of course there are double sometimes triple entendres but they are mostly subtle and need some imagination from the reader. Both plays were written to cover topical issues and so a knowledge of issues facing the Tudors is an advantage.

I read the plays in the Revels Plays series and these two had lengthy introductions by G K Hunter and David Bevington and although they date from 1988 I cannot think that they could be bettered; essential reading before launching into the text itself. There are copious notes on the same page as the text as well as a glossarial Index to the commentary. These plays will probably not make you want to rush to the theatre to see a performance, but I would not mind attending a read through, as unlikely as that might be. This whole package of Lyly’s two earliest plays I would rate as 4 stars.

40NanaCC

>38 baswood: Did you like the first book in the trilogy? I really liked that one the best of the three, and almost feel that the Booker prize, which the third book won, was really for the trilogy as a whole. I think the first book was most worthy.

41baswood

>40 NanaCC: It is some time ago that I read Regeneration before I started blogging on LT. However I did enjoy the first book more, but that may have been because it was fresh and original at the time.

42dchaikin

>39 baswood: enjoyed this. I only just learned that Plutarch's Lives was first translated into English during Elizabeth's reign, hence all the fuss on the new discovery...new info to me.

43baswood

Iain M Banks - Consider Phlebus

Its an Iain M Banks novel rather than an Iain Banks novel and so it is one of his science fiction novels. In fact it was his first published science fiction novel dating from 1987 and the first in his Culture series. It is in the sub genre of Space Opera in that the whole galaxy is background to the story of Bora Horza Gobuchul. Far in the future the humanoids of the Culture are at war with the Idirans described as three-strides-tall-monsters. The Culture have developed machinery/robotics that allows their humanoids to enjoy a more hedonistic lifestyle while the Idirans with their god fearing culture are intent on dominating the galaxy. Bora is an agent of the Idirans because he prefers the God folk monsters rather than the machine dominated lifeless Culture. The novel opens with Bora a prisoner of the Gerontics who are part of the Cultures sphere of influence. Bora is a changer in that over a period of time he can adapt to resemble a humanoid which makes him an excellent assassin. He escapes from the Gerontics and embarks on a series of adventures around the galaxy as an agent of the Indirans.

The novel is loosely held together with Bora’s quest to locate a Mind; an advanced piece of robotic machinery developed by the Culture which has escaped from a battle with the Idirans and is hiding in a tunnel network on one of the dead planets Schar’s world. Bora manages to infiltrate a gang of mercenaries and the second half of the novel takes place in the claustrophobic tunnels of Schar’s world where the team and a captured Culture agent do battle with an elite vanguard of Idirans. The tunnel network with decommissioned trains and impossible odds provides an atmospheric backdrop to the climax of the book.

Banks is at his best in this novel when he creates a scenario where he can unleash some fast paced thriller writing against an imaginative background. The gruesome goings on on the island of Fwi-song or the ingenious drug enhanced game of Damage on Vavatch Orbital on the eve of its destruction and finally in the tunnels of Schar’s world, in each of these stories Bora battles his way through the limits of his physical capabilities in his single minded quest to win and survive. However it is Bank’s ability to carry the reader along with his visualisation of his fantasy environments and his portrayal of his characters that are deep enough for them to emerge from the two dimensional. It is adventure rather than hard science and episodic rather than continuous, but it does have that sense of wonder during its best passages that make it an enjoyable science fiction read which I rate at 3.5 stars.

44dchaikin

>43 baswood: Sounds like imaginative cultural commentary with lots of opportunity for natural tension - and that’s just from your review. I guess I’m intrigued.

46baswood

De la Terre à la Lune (classiques) (French edition) - Jules Verne

Originally published in instalments in the popular Parisien newspaper (Journal des débats politiques et llttéraires) between September and October 1865 after the more famous Journey to the Centre of the Earth a year earlier. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction claims that Verne was one of the two pre-eminent authors in the field of science fiction in the nineteenth century the other being H G Wells. Verne wrote his From the Earth to the Moon some 36 years before Wells’ First Men in the Moon and easily beats it for scientific facts and figures and while Verne might not have had the literary style of Wells he still paints an effective portrait of America just at the end of the Civil War. It is a portrait laced with satire and while the straightforward plot bears no deviation from its title (not a single female character) it still manages to hugely entertain.

The novel opens with a meeting of the American Gun Club in Baltimore and its members are worried about the future, The war has ended, nobody is using artillery, nobody is ordering guns, arms manufactures are losing money: what can be done. The members explore the possibilities of a new war, of wars in foreign countries, but everyone is at peace; something must be done. Its president Impey Barbicane comes up with an idea that will save the club, they will oversee the production of a massive gun that will fire a shell from the earth to the moon. When he announces the new project he is carried shoulder high around the town as the whole of America is gripped with moon fever. Much of the first part of the novel concerns the logistics of building the canon and disputes over the calculation of distances, range and dimensions. Then a telegram is received from Paris sent by Michel Arden who says he is on his way to America and wants the shape of the bullet changed so that it can be hollowed and they can travel inside to the moon. Arden arrives he is a larger than life character and Verne uses him to satirise the french. Arden we learn is a “breaker of windows” an adventurous, courageous, proud man who has no time for details. His enthusiasm matches the Americans and soon they are in agreement to travel together to the moon.

I read the Livre de Poche edition which features 41 illustrations by Henri de Montaut which captures the text superbly and heightens the satire. The illustration of the inner circle of the gun club shows them all with crutches, wooden appendages, hooks instead of hands and steel plated craniums. The pictures of Michel Arden who towers over the Americans are brilliant and really I found myself lost in the details of these pen and ink drawings. Jules Verne’s parodies of Americans and French make great characters, the English it appears are beneath contempt hardly worth the bother as they pour cold water on the magnificent adventure. Part of the interest in reading science fiction before it was called science fiction is to check off the more accurate predictions of the future and Verne seems to have known enough science to make a reasonable stab. Of interest to me was the devastation caused to the earth and its atmosphere by the firing of the huge gun, this was an unexpected consequence of the gung-ho adventurers. Verne’s mix of science, adventure and humour which sometimes turns black hit the right note for me and I am looking forward to reading more of his ‘Voyages extraordinaires' 4 stars.

Originally published in instalments in the popular Parisien newspaper (Journal des débats politiques et llttéraires) between September and October 1865 after the more famous Journey to the Centre of the Earth a year earlier. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction claims that Verne was one of the two pre-eminent authors in the field of science fiction in the nineteenth century the other being H G Wells. Verne wrote his From the Earth to the Moon some 36 years before Wells’ First Men in the Moon and easily beats it for scientific facts and figures and while Verne might not have had the literary style of Wells he still paints an effective portrait of America just at the end of the Civil War. It is a portrait laced with satire and while the straightforward plot bears no deviation from its title (not a single female character) it still manages to hugely entertain.