Oct - Dec 2020: Russians Write the Revolution 1881 - 1922

DiscussãoReading Globally

Aderi ao LibraryThing para poder publicar.

1SassyLassy

Welcome to the last quarter of 2020: Russians Write the Revolution 1881 - 1922

The Assassination of Alexander II, March 13, 1881

The Assassination of Alexander II, March 13, 1881

2SassyLassy

Despite popular history accounts and even some schoolbook summaries, revolutions do not start with a single spark. Long before the tea was thrown into Boston Harbour, or the French queen suggested diet alternatives, popular resistance among the people was building against the respective established orders. Oppression from above, often ruthless, nationalist aims, war, hunger, poverty, religious dissent, and land distribution and ownership; all are fuel for revolutionary fires.

So it was with the series of early twentieth century Russian revolutions in 1905, February 1917 and October 1917, that transformed Russia from a feudal state into the power broker it was for much of the twentieth century.

Long before the 1905 Revolution, resistance to auotcracy was building. A complete overthrow wasn’t necessarily being sought, but a constitutional monarchy seemed to many to be a reasonable goal at that time. Novels, plays, political writing, newspapers and poetry all played their part; an astonishing feat in a country where literacy was estimated to be only between 30 - 40% of the population; a figure that would dramatically increase during and after the revolutions. As time went on, more and more radical ideas gained popularity and it became obvious that autocracy was not the way forward. However, not everyone was seeking change. Some were doing just fine with things as they were, and they wrote too.

1881 is the date selected to start this literary survey. Alexander II was assassinated on March 13th of that year. Ironically, he was the tsar who had passed the Emancipation Edict in 1861, freeing more than 23 million serfs, albeit keeping them on the same lands. His son Alexander III succeeded him. After punishing the perpetrators of the assassination, he immediately clamped down on dissent, establishing the Okhrana or political police, forerunner of the KGB.

1922 is the end year. That year saw the end of the Civil War and the establishment of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on December 30th.

In between these two years, there was an unprecedented amount published.

So it was with the series of early twentieth century Russian revolutions in 1905, February 1917 and October 1917, that transformed Russia from a feudal state into the power broker it was for much of the twentieth century.

Long before the 1905 Revolution, resistance to auotcracy was building. A complete overthrow wasn’t necessarily being sought, but a constitutional monarchy seemed to many to be a reasonable goal at that time. Novels, plays, political writing, newspapers and poetry all played their part; an astonishing feat in a country where literacy was estimated to be only between 30 - 40% of the population; a figure that would dramatically increase during and after the revolutions. As time went on, more and more radical ideas gained popularity and it became obvious that autocracy was not the way forward. However, not everyone was seeking change. Some were doing just fine with things as they were, and they wrote too.

1881 is the date selected to start this literary survey. Alexander II was assassinated on March 13th of that year. Ironically, he was the tsar who had passed the Emancipation Edict in 1861, freeing more than 23 million serfs, albeit keeping them on the same lands. His son Alexander III succeeded him. After punishing the perpetrators of the assassination, he immediately clamped down on dissent, establishing the Okhrana or political police, forerunner of the KGB.

1922 is the end year. That year saw the end of the Civil War and the establishment of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on December 30th.

In between these two years, there was an unprecedented amount published.

3SassyLassy

Many of the intelligentsia of late nineteenth century Russia saw themselves as Europeans, and looked westward for inspiration. Many did not have Russian as their first language, beyond that used to communicate with their household staff. However, the material they chose to write about was starting to change. Many authors were already writing in a realist style, telling what they saw, but now they started to focus that technique on Russian topics.

Nationalism was a huge part of this. In the nineteenth century there was a cultural move away from Europe toward pan slavic topics. Dostoevsky and others called themselves pochvenniki, or people rooted in the soil. The Russian peasantry suddenly became interesting to them, and folklore emerged as a theme in art, music and writing.

Russian writers, unlike many western writers, did not restrict themselves to one format. They often wrote in several formats, moving back and forth from one to another: novels, novellas, plays, poetry and short stories. The short story form, although used by writers like Gogol and Turgenev, was being redirected in the early twentieth century away from realism and toward a more experimental form. Some saw it as a break with the long novel tradition of the past, a more modern expression.

Symbolism, mysticism, magical realism, stream of consciousness, all became new material to use for the hoped for new world.

Writing was a dangerous activity. Censorship was a given, but what was censored often changed. Something written in one year without any political problems could become something to put the writer in exile, prison, or worse in another year. Some writing was done and published in exile. Some was smuggled out of Russia and published elsewhere, often making dates and texts somewhat uncertain.

The following is just a small sample of what is currently available in English. For those lucky enough to read in French, German, Polish, Yiddish or Ukranian, not to mention Russian, the field is much more broad.

The dates here are arbitrary. Many writers who are gods in the Russian literary pantheon do not appear in these lists as their writing was earlier or later. For example, Dostoyevsky, although hugely influential, does not appear, dying just a few days before the assassination of the tsar. Similarly the early work of Tolstoy and other authors does not appear, but is easily found. If your inner anarchist’s reading roams outside these dates, please post anyway.

Just a note on translation. The translator is so important s/he can make or break a reader’s response to a particular book. If one translation doesn’t work, but the book seems otherwise worthwhile, look for a different translator.

Nationalism was a huge part of this. In the nineteenth century there was a cultural move away from Europe toward pan slavic topics. Dostoevsky and others called themselves pochvenniki, or people rooted in the soil. The Russian peasantry suddenly became interesting to them, and folklore emerged as a theme in art, music and writing.

Russian writers, unlike many western writers, did not restrict themselves to one format. They often wrote in several formats, moving back and forth from one to another: novels, novellas, plays, poetry and short stories. The short story form, although used by writers like Gogol and Turgenev, was being redirected in the early twentieth century away from realism and toward a more experimental form. Some saw it as a break with the long novel tradition of the past, a more modern expression.

Symbolism, mysticism, magical realism, stream of consciousness, all became new material to use for the hoped for new world.

Writing was a dangerous activity. Censorship was a given, but what was censored often changed. Something written in one year without any political problems could become something to put the writer in exile, prison, or worse in another year. Some writing was done and published in exile. Some was smuggled out of Russia and published elsewhere, often making dates and texts somewhat uncertain.

The following is just a small sample of what is currently available in English. For those lucky enough to read in French, German, Polish, Yiddish or Ukranian, not to mention Russian, the field is much more broad.

The dates here are arbitrary. Many writers who are gods in the Russian literary pantheon do not appear in these lists as their writing was earlier or later. For example, Dostoyevsky, although hugely influential, does not appear, dying just a few days before the assassination of the tsar. Similarly the early work of Tolstoy and other authors does not appear, but is easily found. If your inner anarchist’s reading roams outside these dates, please post anyway.

Just a note on translation. The translator is so important s/he can make or break a reader’s response to a particular book. If one translation doesn’t work, but the book seems otherwise worthwhile, look for a different translator.

4SassyLassy

Prose

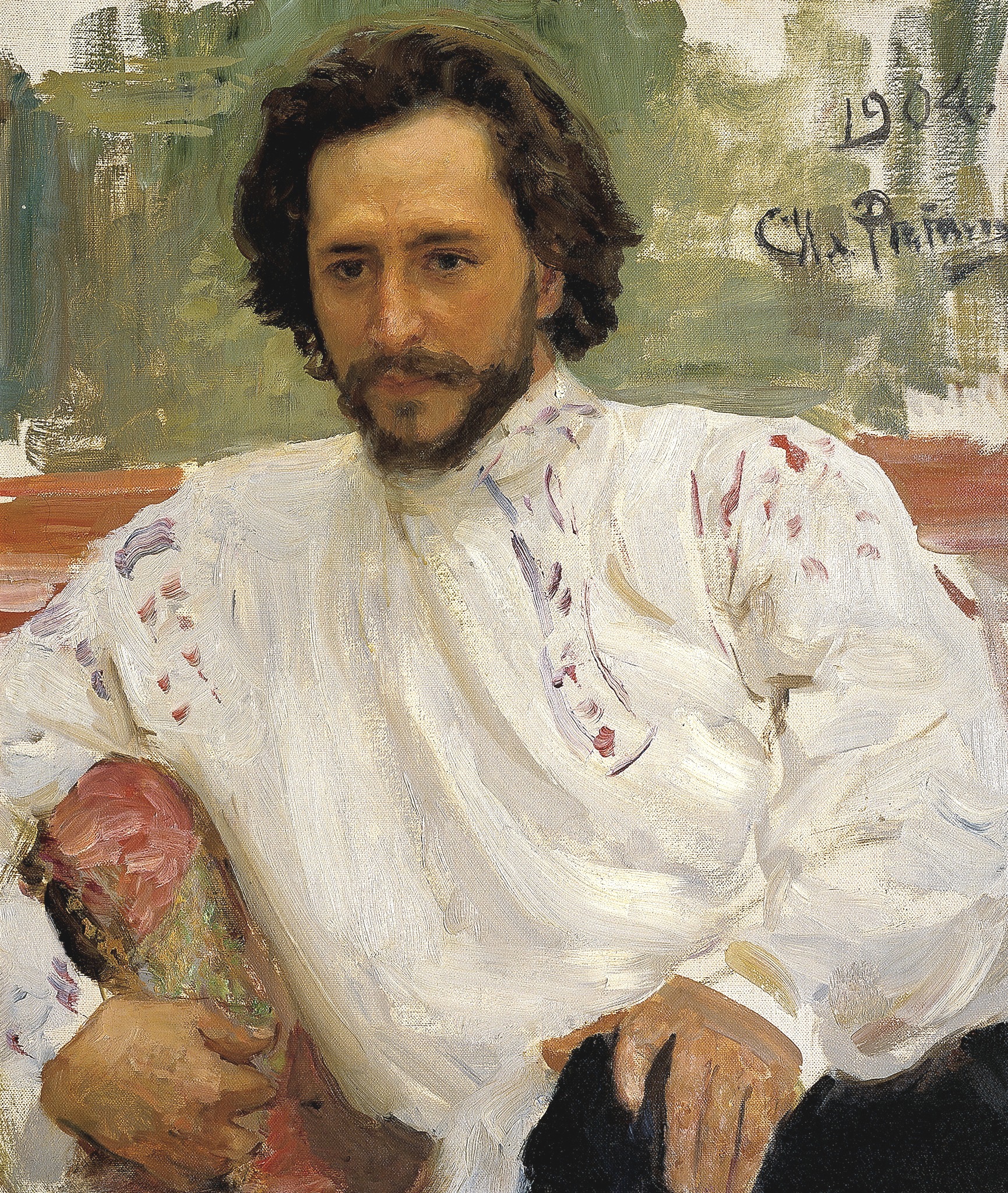

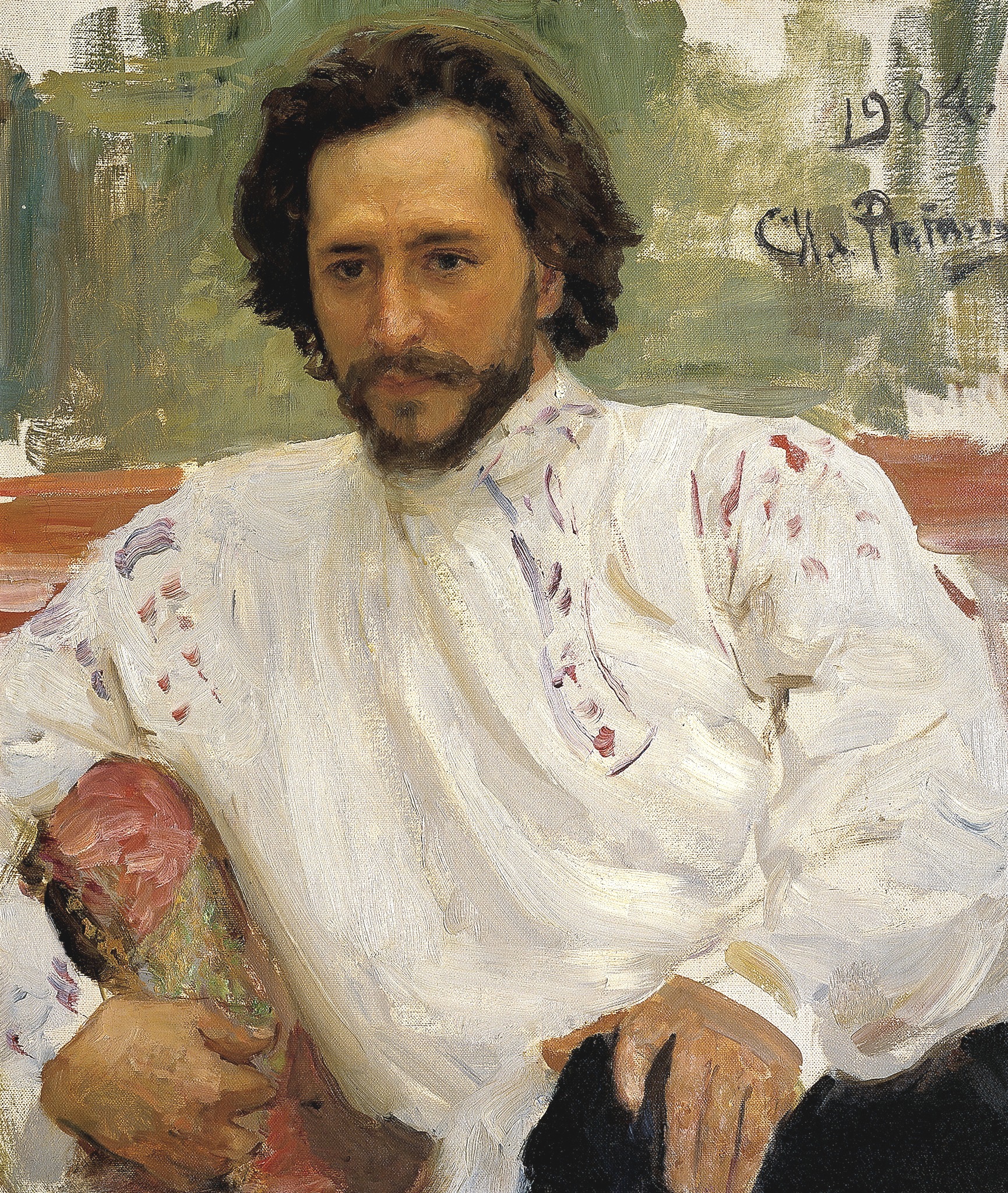

By sheer coincidence this first writer resembles some kind of imaginary idea of a Russian writer

Leonid Nicolayevitch Andreyev by Ilya Repin

Leonid Andreyev 1871 - 1919

was considered by many to be the foremost writer in Russia between the revolutions of 1905 and 1917.

His short stories, novels and plays "explore the world of deprivation and depravity"

The Seven Who were Hanged 1908

The Little Angel and Other Stories - 1916

The Crushed Flower and Other Stories 1916

Satan’s Diary 1919

Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev pen name Andrei Bely 1880 - 1934

The Silver Dove 1910

Petersburg 1913 - a novel of Petersburg in 1905 with magical realism overtones

Selected Essays of Andrey Bely ed Steven Cassedy 1985

David Bergelson 1884 - 1952 (executed on the Night of the Murdered Poets)

Arum vokzal (At the Depot)1909 in A Shtetl and Other Yiddish Novellas 1986

Opgang 1920 (Departing) - decline of the shtetl

When All is Said and Done 1913 novel of the final years of the Russian Empire

The Stories of David Bergelson 1996

Ivan Bunin first Russian to win Nobel Prize for Literature (1933) 1870- 1953, was a realist in the school of Tolstoy and Chekov, an anti Bolshevik

To the Edge of the World and Other Stories 1897

The Village 1910

Dry Valley 1912

The Gentleman from San Francisco 1916

Anton Chekhov 1860 -1904

short stories (over 500)

Motley Stories 1886

In the Twilight 1888 (collection)

The Duel1891

Ward Six 1892

Semen Iushkevich / Semjon Juskevics / Semjon Juschkewitch

Leon Drei serialized 1908-19, book 1922 - a novel with a capitalist antihero protagonist

Aleksandr Kuprin 1870-1938 novelist and short story writer

The Duel 1905

Moloch 1896

The Last Debut 1889

The Garnet Bracelet 1911

Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya pen name Teffi 1872 - 1952

satirist, short story writer

stories collected in Tolstoy, Rasputin, Others, and Me: The Best of Teffi NYRB classics 2016

Leo Tolstoy - 1828 - 1910

realist fiction writing developed in his later works into a reflection of his pacifist Christian beliefs

The Death of Ivan Ilyich 1886

The Kreutzer Sonata 1889

Resurrection 1899 (illustrated by Boris Pasternak’s father Leonid)

Hadji Murat1912

Yevgeny Zamyatin 1884 - 1937

satirist, dystopian

We 1921

By sheer coincidence this first writer resembles some kind of imaginary idea of a Russian writer

Leonid Nicolayevitch Andreyev by Ilya Repin

Leonid Andreyev 1871 - 1919

was considered by many to be the foremost writer in Russia between the revolutions of 1905 and 1917.

His short stories, novels and plays "explore the world of deprivation and depravity"

The Seven Who were Hanged 1908

The Little Angel and Other Stories - 1916

The Crushed Flower and Other Stories 1916

Satan’s Diary 1919

Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev pen name Andrei Bely 1880 - 1934

The Silver Dove 1910

Petersburg 1913 - a novel of Petersburg in 1905 with magical realism overtones

Selected Essays of Andrey Bely ed Steven Cassedy 1985

David Bergelson 1884 - 1952 (executed on the Night of the Murdered Poets)

Arum vokzal (At the Depot)1909 in A Shtetl and Other Yiddish Novellas 1986

Opgang 1920 (Departing) - decline of the shtetl

When All is Said and Done 1913 novel of the final years of the Russian Empire

The Stories of David Bergelson 1996

Ivan Bunin first Russian to win Nobel Prize for Literature (1933) 1870- 1953, was a realist in the school of Tolstoy and Chekov, an anti Bolshevik

To the Edge of the World and Other Stories 1897

The Village 1910

Dry Valley 1912

The Gentleman from San Francisco 1916

Anton Chekhov 1860 -1904

short stories (over 500)

Motley Stories 1886

In the Twilight 1888 (collection)

The Duel1891

Ward Six 1892

Semen Iushkevich / Semjon Juskevics / Semjon Juschkewitch

Leon Drei serialized 1908-19, book 1922 - a novel with a capitalist antihero protagonist

Aleksandr Kuprin 1870-1938 novelist and short story writer

The Duel 1905

Moloch 1896

The Last Debut 1889

The Garnet Bracelet 1911

Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya pen name Teffi 1872 - 1952

satirist, short story writer

stories collected in Tolstoy, Rasputin, Others, and Me: The Best of Teffi NYRB classics 2016

Leo Tolstoy - 1828 - 1910

realist fiction writing developed in his later works into a reflection of his pacifist Christian beliefs

The Death of Ivan Ilyich 1886

The Kreutzer Sonata 1889

Resurrection 1899 (illustrated by Boris Pasternak’s father Leonid)

Hadji Murat1912

Yevgeny Zamyatin 1884 - 1937

satirist, dystopian

We 1921

5SassyLassy

Poetry

Anna Akhmatova by Nathan Altman 1915

Russia may seem to be a nation of poets. By chance, the time frame of this quarter, the late 19th C to the 1920s is considered the ‘Silver Age’ of Russian poetry. It was characterized by a move away from realism to symbolism and imagination, sometimes incorporating mysticism. Poets also started to form groups for different stylistic movements.

Osip Mandelstam said “Only in Russia is poetry respected, it gets people killed.”

His poem ‘Stalin Epigram’ (1933) had him arrested and interrogated.

Anna Akhmatova1889 - 1966

founder with Mandelstam and Gorodetsky of the Guild of Poets, concrete poets as opposed to the symbolists

Evening 1912

Rosary 1914

White Flock 1917

Anno domini MCMXXI 1921

Wayside Grass 1921

_____

Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev pen name Andrei Bely 1880- 1932

symbolist poet

Gold in Azure 1904 - Jason and the Argonauts' quest for the golden fleece

_____

Alexander Blok 1880 - 1921

symbolist poet

Poems of Sophia 1904

The Stranger 1906

The Twelve 1918 12 Red Guards as 12 apostles of revolution

_____

Sasha Chorny 1880 - 1932 wrote for magazine Satirikon

satirist

https://ruverses.com/sasha-chorny/

_____

David Hofstein 1889 - 1952 executed on 'The Night of the Murdered Poets'

Troyer (Tears) 1922 illustrated by Chagall

_____

Osip Mandelstam 1891 - 1938 died in the Gulag

The Stone 1913 collection reissued 1916 with additional poems

The Meaning of Acmeism 1913 published 1919 manifesto for the Poets’ Guild

_____

Vladimir Mayakovsky 1893 - 1930 suicide

A Cloud in Trousers 1915

Backbone Flute 1915

The War and the World 1917

The Man 1918

150 000 000 - 1921

_____

Nikolai Minsky 1885 - 1937

symbolist poet

From the Gloom to the Light 1922

_____

Sonya Yakovlevna Parnokh 1885 -1933, pen name for journalism Andrei Polianin

work suppressed during Soviet period - she had written openly about her lesbian relationships

Poems 1916

Roses of Pieria 1922

_____

Boris Pasternak 1890 - 1960

Nobel Prize 1958

Twin in the Clouds 1914

Over the Barriers 1916

Themes and Variations 1917

My Sister, Life 1917, pub 1922

_____

Marina Tsvetaeva 1892 - 1941 suicide

lyric poet, but also satirist

Evening Album 1910

The Magic Lantern 1912

Mileposts 1921

_____

Maximilian Voloshin 1877 - 1932

banned during Stalin’s time so little known now but popular in his time

poetry linked Civil War Russia to mythical past

_____

Sergei Yesenin 1895 - 1925

hugely popular ‘peasant poet’

The Last Poet of the Village: Selected Poems by Sergei Ysesnin trans Anton Yakovlev 2019

Collected Poems: Volume One ed Will Jonson 2014

Collected Poems: Volume Two ed Will Jonson 2014

_____________

Collection:

The Stray Dog Cabaret: A Book of Russian Poems NYRB Classics 2006

Anna Akhmatova by Nathan Altman 1915

Russia may seem to be a nation of poets. By chance, the time frame of this quarter, the late 19th C to the 1920s is considered the ‘Silver Age’ of Russian poetry. It was characterized by a move away from realism to symbolism and imagination, sometimes incorporating mysticism. Poets also started to form groups for different stylistic movements.

Osip Mandelstam said “Only in Russia is poetry respected, it gets people killed.”

His poem ‘Stalin Epigram’ (1933) had him arrested and interrogated.

Anna Akhmatova1889 - 1966

founder with Mandelstam and Gorodetsky of the Guild of Poets, concrete poets as opposed to the symbolists

Evening 1912

Rosary 1914

White Flock 1917

Anno domini MCMXXI 1921

Wayside Grass 1921

_____

Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev pen name Andrei Bely 1880- 1932

symbolist poet

Gold in Azure 1904 - Jason and the Argonauts' quest for the golden fleece

_____

Alexander Blok 1880 - 1921

symbolist poet

Poems of Sophia 1904

The Stranger 1906

The Twelve 1918 12 Red Guards as 12 apostles of revolution

_____

Sasha Chorny 1880 - 1932 wrote for magazine Satirikon

satirist

https://ruverses.com/sasha-chorny/

_____

David Hofstein 1889 - 1952 executed on 'The Night of the Murdered Poets'

Troyer (Tears) 1922 illustrated by Chagall

_____

Osip Mandelstam 1891 - 1938 died in the Gulag

The Stone 1913 collection reissued 1916 with additional poems

The Meaning of Acmeism 1913 published 1919 manifesto for the Poets’ Guild

_____

Vladimir Mayakovsky 1893 - 1930 suicide

A Cloud in Trousers 1915

Backbone Flute 1915

The War and the World 1917

The Man 1918

150 000 000 - 1921

_____

Nikolai Minsky 1885 - 1937

symbolist poet

From the Gloom to the Light 1922

_____

Sonya Yakovlevna Parnokh 1885 -1933, pen name for journalism Andrei Polianin

work suppressed during Soviet period - she had written openly about her lesbian relationships

Poems 1916

Roses of Pieria 1922

_____

Boris Pasternak 1890 - 1960

Nobel Prize 1958

Twin in the Clouds 1914

Over the Barriers 1916

Themes and Variations 1917

My Sister, Life 1917, pub 1922

_____

Marina Tsvetaeva 1892 - 1941 suicide

lyric poet, but also satirist

Evening Album 1910

The Magic Lantern 1912

Mileposts 1921

_____

Maximilian Voloshin 1877 - 1932

banned during Stalin’s time so little known now but popular in his time

poetry linked Civil War Russia to mythical past

_____

Sergei Yesenin 1895 - 1925

hugely popular ‘peasant poet’

The Last Poet of the Village: Selected Poems by Sergei Ysesnin trans Anton Yakovlev 2019

Collected Poems: Volume One ed Will Jonson 2014

Collected Poems: Volume Two ed Will Jonson 2014

_____________

Collection:

The Stray Dog Cabaret: A Book of Russian Poems NYRB Classics 2006

6SassyLassy

Logo of the Stray Dog Café

Theatre

Theatre was exceptionally popular not only in St Petersburg and Moscow, but also in other centres such as Kyiv, Odessa and Minsk. One of the most famous meeting spots for playwrights and poets was the Stray Dog Café in St Petersburg (1911 - 1915).

Alexander Pushkin and Nikola Gogol (The Government Inspector) were realist writers in the early to middle nineteenth century, who influenced play writing in a major way for decades to come. Their plays are still being performed today. Some of the people they influenced:

Anton Chekhov 1860 -1904

prolific playwright and short story writer

Ivanov 1888

The Seagull 1896

Uncle Vanya 1900

Three Sisters 1901

The Cherry Orchard 1904

_____

Maxim Gorky 1868 - 1936 playwright and novelist

one of founders of socialist realism school of literature

all around involvement in culture and politics

_____

Vladimir Mayakovsky 1893 - 1930 suicide

playwright, poet, silent screen actor

-Mystery Bouffe 1921 socialist drama celebrating proletarian triumph of the 'unclean' over the 'clean' bourgeoisie

_____

Konstantin Stanislavski 1863 - 1938

developed the role of director and the school of method acting

7SassyLassy

Religious

Lou Andreas-Salomé 1861 - 1937

Sex and Religion 2 texts, 1917 and 1922, trans 2016 by Maike Oergel and Kristine Jennings

_____

Nikolai Minskii 1885 - 1937

The Religion of the Future 1905

_____

Leo Tolstoy 1828 - 1910

The Kingdom of God is Within You published in Germany in 1894 after being banned in Russia

pacifist plea for non violent resistance

Lou Andreas-Salomé 1861 - 1937

Sex and Religion 2 texts, 1917 and 1922, trans 2016 by Maike Oergel and Kristine Jennings

_____

Nikolai Minskii 1885 - 1937

The Religion of the Future 1905

_____

Leo Tolstoy 1828 - 1910

The Kingdom of God is Within You published in Germany in 1894 after being banned in Russia

pacifist plea for non violent resistance

8SassyLassy

Title page of 1905 edition of Chernyshevsky's What is to Be Done?

Political Writings

It would be hard to look at this period of Russian writing without considering works devoted to politics.

Political thought , no matter what its underlying ideology, is in constant evolution. One of the leading titles influencing the writings below was Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s 1863 novel What is to be Done?, written in prison. It advocated the bypass of capitalism on the road to a communal socialism. Chernyshevsky is still read today.

_____

Sergei Kravchinskii, revolutionary name Stepniak 1851 - 1894

assassin of General Mezentsov who was head of the secret police (1878)

Underground Russia: Revolutionary Profiles and Sketches from Life 1883

_____

Piotr Kropotkin 1842 - 1921 anarchist prince

In Russian and French Prisons 1887

Memoirs of a Revolutionist 1899

Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution 1902

_____

Vladimir Illyich Lenin 1870 - 1924

What is to be Done? Burning Questions of our Movement 1902

https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/

_____

Vladimir Solovyov 1853 - 1900

philosopher active in spiritual thinking at end of 19th C Russia

War, Progress, and the End of History: Three Conversations, Including a Short Story of the Anti-Christ 1915

_____

Leon Trotsky

1905 pub 1908-1909 in Germany, 1922 in Russia

Trotsky’s account of the 1905 revolution and backroom machinations

9SassyLassy

Diaries, Memoirs and Letters

There's nothing like snooping in people's personal accounts, no matter how self-serving, to get an idea of who they really are. Here is just a taste:

Lou Andreas - Salomé 1861 - 1937

Russian born psychoanalyst and essayist

Rilke and Andreas-Salomé: A Love Story in Letters

_____

Ivan Bunin

Cursed Days - diary excerpts of the years 1918 - 1920, first serialized in Paris 1925 -1926

_____

Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya pen name Teffi 1872 - 1952

Memories: from Moscow to the Black Sea her account of her flight from Russia to Istanbul in 1919

_____

Maria Tsvetaeva 1892 - 1941

Earthly Signs: Moscow Diaries 1917-1922 ed James Gambrell NYRB classics

There's nothing like snooping in people's personal accounts, no matter how self-serving, to get an idea of who they really are. Here is just a taste:

Lou Andreas - Salomé 1861 - 1937

Russian born psychoanalyst and essayist

Rilke and Andreas-Salomé: A Love Story in Letters

_____

Ivan Bunin

Cursed Days - diary excerpts of the years 1918 - 1920, first serialized in Paris 1925 -1926

_____

Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya pen name Teffi 1872 - 1952

Memories: from Moscow to the Black Sea her account of her flight from Russia to Istanbul in 1919

_____

Maria Tsvetaeva 1892 - 1941

Earthly Signs: Moscow Diaries 1917-1922 ed James Gambrell NYRB classics

10SassyLassy

Just a Little Bit too Early, Some Writings of Influence

Mikhail Bakunin 1814 - 1876

anarchist, socialist, collectivist, opponent of Marx

God and the State 1871 published posthumously in Geneva 1882

_____

Nikolay Chernyshevsky

What is to Be Done? 1863 see above >8 SassyLassy:

_____

Fyodor Dostoevsky 1821 - 9 Feb 1881 wrote 15 novels and novellas plus 17 short stories

The House of the Dead 1861 prison experiences in Siberia

Notes from Underground 1864 novel challenging various political ideologies prevalent at the time

_____

Alexander Herzen 1812 - 1870 advocate of agrarian socialism

My Past and Thoughts: Memoirs Vol 1 and 2

Who is to Blame? Herzen 1846 (novel)

Mikhail Bakunin 1814 - 1876

anarchist, socialist, collectivist, opponent of Marx

God and the State 1871 published posthumously in Geneva 1882

_____

Nikolay Chernyshevsky

What is to Be Done? 1863 see above >8 SassyLassy:

_____

Fyodor Dostoevsky 1821 - 9 Feb 1881 wrote 15 novels and novellas plus 17 short stories

The House of the Dead 1861 prison experiences in Siberia

Notes from Underground 1864 novel challenging various political ideologies prevalent at the time

_____

Alexander Herzen 1812 - 1870 advocate of agrarian socialism

My Past and Thoughts: Memoirs Vol 1 and 2

Who is to Blame? Herzen 1846 (novel)

11SassyLassy

Just a Little Bit too Late - Some Writers who Lived through it and Wrote on it Later

Mikhail Bulgakov 1891 - 1940

The White Guard 1924 1918-19 Civil War in Kyiv

The Master and Margarita started in 1928, published 1967 (translation is everything with this novel)

_____

Osip Mandelstam 1891 - 1938

The Noise of Time 1925 in The Noise of Time: Selected Prose 2002 trans Clarence Brown

_____

Boris Pasternak 1890 - 1960

Nobel Prize 1958

Doctor Zhivago finished 1956 (okay more than a lttle bit late but parts were written in the 1910s and 1920s)

_____

Mikhail Sholokov - 1905 - 1984

Nobel Prize 1965

And Quiet Flows the Don 1928

The Don Flows Home to the Sea 1940

Mikhail Bulgakov 1891 - 1940

The White Guard 1924 1918-19 Civil War in Kyiv

The Master and Margarita started in 1928, published 1967 (translation is everything with this novel)

_____

Osip Mandelstam 1891 - 1938

The Noise of Time 1925 in The Noise of Time: Selected Prose 2002 trans Clarence Brown

_____

Boris Pasternak 1890 - 1960

Nobel Prize 1958

Doctor Zhivago finished 1956 (okay more than a lttle bit late but parts were written in the 1910s and 1920s)

_____

Mikhail Sholokov - 1905 - 1984

Nobel Prize 1965

And Quiet Flows the Don 1928

The Don Flows Home to the Sea 1940

12SassyLassy

Boris Pasternak by Bill Mauldin, won the 1959 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning

Caption says "I won the Nobel Prize for Literature: What was your Crime?"

A Miscellany of Further Reading

Whole libraries have been filled with books on this era. Indeed some could be filled with books on just one topic, like Trotsky, or the last Romanovs.

History

Isaiah Berlin

Russian Thinkers 1978, 2nd edition revised by Henry Hardy 2008

Berlin's thoughts on Tolstoy, Herzen, Bakunin, Turgenev and others

_____

Orlando Figes

A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1881-1924 1996

Natasha's Dance: A Cultural History of Russia 2002 interweaves Russian art, history, literature, music and theatre from the 18th century to the Soviet era, including the work of Russians in exile

_____

Richard Pipes a master historian - even though this history is older, it is well worth reading

The Russian Revolution 1990

if that's too long, try A Concise History of the Russian Revolution 1996

There is also an interview with Pipes on this book in Cahiers du Monde Russe, Issue 58/1-2 (the interview is in English) which can be found online but the url will not copy

_____

Douglas Smith

Former People: The Final Days of the Russian Aristocracy 2012 book documenting its systematic destruction

_____

Literature

NYT What Makes the Russian Literature of the 19th Century so Distinctive?

1915 survey by Piotr Kropotkin

Woolf and Russian Literature

small section on Russian Jewish writing from the late 19th to early 20th centuries

_________

Political

New York Times report on the Emancipation Manifesto 1861

Quick Timeline of the Russian Revolution

Education, Literacy and the Russian Revolution

13Dilara86

I am looking forward to this quarter! I've had a look on my library's website, and requested Requiem and Poem Without a Hero (which I now realise was written in the thirties - never mind!) by Anna Akhmatova and a CD of Russian music from the twenties to start with. I might also read Doctor Zhivago again. It wasn't written in the right era, but the action takes place during the revolution. I feel I didn't give a chance the first time round. My mum loved it and pushed it on me, but I was probably too young to appreciate it.

14spiralsheep

>3 SassyLassy: The first five segments up and already a great introduction. Thank you.

"Just a note on translation. The translator is so important s/he can make or break a reader’s response to a particular book. If one translation doesn’t work, but the book seems otherwise worthwhile, look for a different translator."

Very true.

A quick scan of my tbr pile shows only two contenders and neither of them especially relevant but I've been reading Belarus related books anyway so I might try Marc Chagall's autobiographical My Life. The other book is later and would only squeeze in to this topic as a novel relevant to the Soviet agricultural revolution in Asia.

"Just a note on translation. The translator is so important s/he can make or break a reader’s response to a particular book. If one translation doesn’t work, but the book seems otherwise worthwhile, look for a different translator."

Very true.

A quick scan of my tbr pile shows only two contenders and neither of them especially relevant but I've been reading Belarus related books anyway so I might try Marc Chagall's autobiographical My Life. The other book is later and would only squeeze in to this topic as a novel relevant to the Soviet agricultural revolution in Asia.

15Dilara86

>14 spiralsheep: The other book is later and would only squeeze in to this topic as a novel relevant to the Soviet agricultural revolution in Asia.

Not to derail, but what is this book? I'm still interested in titles that fit the 2019 Q3 theme Between Giants: Central Asian Border Regions...

Not to derail, but what is this book? I'm still interested in titles that fit the 2019 Q3 theme Between Giants: Central Asian Border Regions...

16spiralsheep

>15 Dilara86: I'm sure you've already heard of Jamilia and many people here have read it. I've also got the new English translation of Sovietistan on hold at the library. I've also recently found a few poems by two contemporary Turkmen poets in exile, and my list says I've also read some poems/short prose pieces by Uzbeks this year (but I can't remember everything without googling).

Ak Welsapar:

https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/tag/turkmenistan/

ETA: https://www.nationalpoetrylibrary.org.uk/online-poetry/poems/night-dropped-stars...

There was another contemporary exiled male poet I can't recall now but I'll have a think.

I haven't read this by Batyr Berdyev:

http://provetheyarealive.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Batyr-Berdyev_Parting_so...

Might be worth googling for Annasoltan Kekilova.

ETA: https://james-womack.com/2020/03/01/kekilovas-scarf/

The image can be enlarged:

https://twitter.com/MPTmagazine/status/1202903874534858752/

Older "classic" "national" poet: Magtymguly Pyragy.

Rauf Parfi:

https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/tag/uzbekistan/

Hamid Ismailov:

https://www.asymptotejournal.com/blog/2016/04/12/translation-tuesday-a-corpse-by...

Ak Welsapar:

https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/tag/turkmenistan/

ETA: https://www.nationalpoetrylibrary.org.uk/online-poetry/poems/night-dropped-stars...

There was another contemporary exiled male poet I can't recall now but I'll have a think.

I haven't read this by Batyr Berdyev:

http://provetheyarealive.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Batyr-Berdyev_Parting_so...

Might be worth googling for Annasoltan Kekilova.

ETA: https://james-womack.com/2020/03/01/kekilovas-scarf/

The image can be enlarged:

https://twitter.com/MPTmagazine/status/1202903874534858752/

Older "classic" "national" poet: Magtymguly Pyragy.

Rauf Parfi:

https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/tag/uzbekistan/

Hamid Ismailov:

https://www.asymptotejournal.com/blog/2016/04/12/translation-tuesday-a-corpse-by...

17NinieB

Hello all, I am new to this group, and I'm impressed by the extensive reading you have been doing and have planned. I will try to read something this quarter--a couple of options in my TBR are Mikhail Artsybashev's Sanine (1907) and Ivan Turgenev's Virgin Soil (1877), which is a little early on the date but is about middle-class revolutionaries.

18spiralsheep

>17 NinieB: Hi, and welcome!

19spiralsheep

>15 Dilara86: My apologies to SassyLassy for this but I guess it's of interest to several RG members reading this thread so....

Annasoltan Kekilova

The image can be enlarged:

https://twitter.com/MPTmagazine/status/1202903874534858752/

https://james-womack.com/2020/03/01/kekilovas-scarf/

Annasoltan Kekilova

The image can be enlarged:

https://twitter.com/MPTmagazine/status/1202903874534858752/

https://james-womack.com/2020/03/01/kekilovas-scarf/

20ELiz_M

I was thinking nyrb might have several books that fit this theme/era and found this one:

Earthly Signs: Moscow Diaries, 1917-1922 by Marina Tsvetaeva

Earthly Signs: Moscow Diaries, 1917-1922 by Marina Tsvetaeva

21NinieB

>18 spiralsheep: Thanks!

22SassyLassy

Thanks all for the enthusiastic response. Naturally I'm excited about this quarter.

>13 Dilara86: Timeline doesn't matter with someone like Akhmatova - it's always time to read her and I love the idea of doing it to music.

Parts of Doctor Zhivago were written in this timeline and I imagine Pasternak had other worries, so the same applies to him.

>14 spiralsheep: Chagall, excellent

>16 spiralsheep: >19 spiralsheep: Thanks for those links - no apologies necessary!

>17 NinieB: Welcome

>20 ELiz_M: Had that for my unfinished posts - see >9 SassyLassy: above-, so happy to see someone else thinking of it

Odd that there are two posts numbered 20

>13 Dilara86: Timeline doesn't matter with someone like Akhmatova - it's always time to read her and I love the idea of doing it to music.

Parts of Doctor Zhivago were written in this timeline and I imagine Pasternak had other worries, so the same applies to him.

>14 spiralsheep: Chagall, excellent

>16 spiralsheep: >19 spiralsheep: Thanks for those links - no apologies necessary!

>17 NinieB: Welcome

>20 ELiz_M: Had that for my unfinished posts - see >9 SassyLassy: above-, so happy to see someone else thinking of it

Odd that there are two posts numbered 20

23SassyLassy

We all need a break from time to time, so here are two completely escapist, not entirely historically correct Russian series, dubbed into English.

Trotsky

a 2017 Russian production for the centenary of the Russian Revolution, available on Netflix

won 8 awards from The Association of Film and Television Producers (Russia) so it must have pleased someon

directors Alexander Kott and Konstantin Statsky

starring Konstantin Khabensky, Olga Sutulova and Max Matveev

plot - Trotsky is in exile in Mexico, waiting for his assassin. He tells his life to a journalist in a series of flashbacks for an imaginary political testament.

_____

The Road to Calvary based on a 1921 - 1940 trilogy by Alexei Tolstoy 1883 - 1945 also on Netflix

a 2017 Russian production following a family in St Petersburg during the years 1914 - 1919

stars Yuliya Snigir, Anna Chipovskaya, Leondid Bichevin and Pavel Trubiner

since it ends in 1919 and the book goes later, there is room for a sequel

Trotsky

a 2017 Russian production for the centenary of the Russian Revolution, available on Netflix

won 8 awards from The Association of Film and Television Producers (Russia) so it must have pleased someon

directors Alexander Kott and Konstantin Statsky

starring Konstantin Khabensky, Olga Sutulova and Max Matveev

plot - Trotsky is in exile in Mexico, waiting for his assassin. He tells his life to a journalist in a series of flashbacks for an imaginary political testament.

_____

The Road to Calvary based on a 1921 - 1940 trilogy by Alexei Tolstoy 1883 - 1945 also on Netflix

a 2017 Russian production following a family in St Petersburg during the years 1914 - 1919

stars Yuliya Snigir, Anna Chipovskaya, Leondid Bichevin and Pavel Trubiner

since it ends in 1919 and the book goes later, there is room for a sequel

24thorold

Thanks for setting this up, SassyLassy! Russia's one of my literary blind spots, and I don't have anything Russian on the TBR pile at all at the moment, so there's a lot there I could have a go at. The only vaguely relevant things I've read in the last few years are Red cavalry and Kropotkin's memoirs.

Akhmatova and Lou Andreas-Salomé are writers I've had my eye on for a while, I hope to get to them. (I did study Akhmatova's "Requiem" on one of my long-ago courses, but that's from much later in her career, outside the time-frame.)

I've got Natasha's Dance on order.

Akhmatova and Lou Andreas-Salomé are writers I've had my eye on for a while, I hope to get to them. (I did study Akhmatova's "Requiem" on one of my long-ago courses, but that's from much later in her career, outside the time-frame.)

I've got Natasha's Dance on order.

25LolaWalser

Thanks, Sassy, great job.

As it happens, I'm reading Gorky's The Artamonovs at the moment, topically relevant but completed in 1924 (Tolstoy gave him the idea at the turn of the century).

I'd mention Alexander Herzen's memoirs as another source for understanding the cultural and political landscape from which various reformist-to-revolutionary oppositions to tsarism emerged.

Since there is a rubric "Religion", it seems necessary to mention at least two hugely influential figures (to this day) who straddled, as Russians in particular seem apt to do, mysticism, philosophy and politics: Vladimir Solovyov and Nikolai Berdyaev (as I don't know what or how available anything of theirs might be, I'm going with author touchstones).

As an antidote to the conservative accounts above of the October revolution, China Miéville's October.

I'd like to concentrate on early Russian feminists but I'm afraid they probably won't be easy to find in English. I think there's a book of Alexandra Kollontai's stories (in German published in 1922?--Wege der Liebe, Love's paths), and Modern Language Association brought out Sofya Kovalevskaya's Nihilist Girl. Kovalevskaya, by the way, is one of the few famous female mathematicians.

As it happens, I'm reading Gorky's The Artamonovs at the moment, topically relevant but completed in 1924 (Tolstoy gave him the idea at the turn of the century).

I'd mention Alexander Herzen's memoirs as another source for understanding the cultural and political landscape from which various reformist-to-revolutionary oppositions to tsarism emerged.

Since there is a rubric "Religion", it seems necessary to mention at least two hugely influential figures (to this day) who straddled, as Russians in particular seem apt to do, mysticism, philosophy and politics: Vladimir Solovyov and Nikolai Berdyaev (as I don't know what or how available anything of theirs might be, I'm going with author touchstones).

As an antidote to the conservative accounts above of the October revolution, China Miéville's October.

I'd like to concentrate on early Russian feminists but I'm afraid they probably won't be easy to find in English. I think there's a book of Alexandra Kollontai's stories (in German published in 1922?--Wege der Liebe, Love's paths), and Modern Language Association brought out Sofya Kovalevskaya's Nihilist Girl. Kovalevskaya, by the way, is one of the few famous female mathematicians.

26SassyLassy

>25 LolaWalser: Happy to see you here and was hoping you would come up with more recommendations!

I had looked at Vladimir Solovyov and then left him out when I should have included him. I suspect there are others in that category lost in my notes.

A Story of Anti-Christ 1900

A Justification of the Good 1918

War, Progress, and the End of History: Three Conversations 1915 (I specifically remember noting this title, who knows where it went!)

_____________

Nikolai Berdyaev thanks for that recommendation

prolific writer in philosophy

an idea of his range:

The New Religious Consciousness and Society 1907

The Spiritual Crisis of the Intelligentsia 1910

The Crisis of Art 1918

Dostoevsky: An Interpretation 1921

_____

Thanks for the Miéville recommendation as well. It looks like a needed balance to the histories above, as well as being a more modern work.

Love the idea of chasing down early Russian feminists. Lou Andreas-Salomé looked interesting, but more are needed. Can we count Emma Goldman?

i'm interested in reading Alexander Herzen's memoirs (see also >10 SassyLassy: above). In an earlier life agrarian socialism was required reading.

_____

>24 thorold: Russia's one of my literary blind spots How can that be?!

Seriously though, how did you escape Isaiah Berlin?

Gorky would be one of my blind spots, but I may find it hard to resist a title like The Life of a Useless Man from 1908,, just to see how the protagonist was deemed useless.

I had looked at Vladimir Solovyov and then left him out when I should have included him. I suspect there are others in that category lost in my notes.

A Story of Anti-Christ 1900

A Justification of the Good 1918

War, Progress, and the End of History: Three Conversations 1915 (I specifically remember noting this title, who knows where it went!)

_____________

Nikolai Berdyaev thanks for that recommendation

prolific writer in philosophy

an idea of his range:

The New Religious Consciousness and Society 1907

The Spiritual Crisis of the Intelligentsia 1910

The Crisis of Art 1918

Dostoevsky: An Interpretation 1921

_____

Thanks for the Miéville recommendation as well. It looks like a needed balance to the histories above, as well as being a more modern work.

Love the idea of chasing down early Russian feminists. Lou Andreas-Salomé looked interesting, but more are needed. Can we count Emma Goldman?

i'm interested in reading Alexander Herzen's memoirs (see also >10 SassyLassy: above). In an earlier life agrarian socialism was required reading.

_____

>24 thorold: Russia's one of my literary blind spots How can that be?!

Seriously though, how did you escape Isaiah Berlin?

Gorky would be one of my blind spots, but I may find it hard to resist a title like The Life of a Useless Man from 1908,, just to see how the protagonist was deemed useless.

27thorold

>26 SassyLassy: Seriously though, how did you escape Isaiah Berlin?

It seems extraordinary to me too with hindsight; I’m here to tell you that it can be done! He must have been just about the most famous thinker in the university when I was there, but at that point I probably wouldn’t even have recognised him if I’d been standing behind him in the queue at Blackwell’s. I don’t think I’ve ever read more than two or three essays.

It seems extraordinary to me too with hindsight; I’m here to tell you that it can be done! He must have been just about the most famous thinker in the university when I was there, but at that point I probably wouldn’t even have recognised him if I’d been standing behind him in the queue at Blackwell’s. I don’t think I’ve ever read more than two or three essays.

28spiphany

I want to mention Gaito Gazdanov, an emigré writer who settled in Paris. He fought for the White Army and his earlier works, though published after the end of the Civil War, reflect on this period, e.g. The Spectre of Alexander Wolf.

Apart from that, I didn't think I had much on my shelf that applied to this period (most of my Russian collection seems to be either Soviet/post-Soviet era or mid-nineteenth-century romanticist-fantastic), but it looks like I may get to dust off my never-very-fluent Russian skills, as I have an e-book with some stories by Teffi and another with stories by Alexander Kuprin (I read and loved his story Olesya years ago and have long intended to read more by him).

And I have some anthologies in translation that include stories by, for example, Nikolai Leskov; some of his later work just barely squeaks in the period under consideration (The Steel Flea is a delightful tale which I recommend regardless of whether it technically qualifies). Leo Tolstoy is represented, too, though his later writing tends to be somewhat too moralizing for my taste, and of course Anton Chekhov (no moralizing, but I've already read a lot by him).

I also found a verse play by Marina Tsvetaeva, Phoenix, and a volume on Mayakovsky for Russian learners which I've been too intimidated by to tackle as of yet. Also some satires by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, who is somewhat too early, but seems to anticipate some of the social developments that culminated in the Revolution.

Apart from that, I didn't think I had much on my shelf that applied to this period (most of my Russian collection seems to be either Soviet/post-Soviet era or mid-nineteenth-century romanticist-fantastic), but it looks like I may get to dust off my never-very-fluent Russian skills, as I have an e-book with some stories by Teffi and another with stories by Alexander Kuprin (I read and loved his story Olesya years ago and have long intended to read more by him).

And I have some anthologies in translation that include stories by, for example, Nikolai Leskov; some of his later work just barely squeaks in the period under consideration (The Steel Flea is a delightful tale which I recommend regardless of whether it technically qualifies). Leo Tolstoy is represented, too, though his later writing tends to be somewhat too moralizing for my taste, and of course Anton Chekhov (no moralizing, but I've already read a lot by him).

I also found a verse play by Marina Tsvetaeva, Phoenix, and a volume on Mayakovsky for Russian learners which I've been too intimidated by to tackle as of yet. Also some satires by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, who is somewhat too early, but seems to anticipate some of the social developments that culminated in the Revolution.

29LolaWalser

>26 SassyLassy:

Oops, apologies for missing the Herzen ref before. This is a fascinating topic but I'm afraid I bring more appetite than knowledge to it--looking forward to what everyone unearths.

Just a quick warning I forgot yesterday, not being in the habit of reading e-books myself--in case anyone finds Solovyov and Berdyaev online, perhaps it's not amiss to make sure the website is a known public database or academic resource.

As cornerstone thinkers of the Russian right, it's not unusual to see neonazi sites peddling their texts in pamphlet form etc.

And, just so I don't leave the impression they speak only to the right, it must be noted that their Great-Russian nationalism and Russian-Orthodox messianism is widespread, really popular (even beyond Russia...)

I may find it hard to resist a title like The Life of a Useless Man

Hey, if you do, I'll join you on that. Had the same reaction for ages. :)

>27 thorold:

Have you read Mikhail Kuzmin? Not a revolutionary in the conventional sense so not a great fit to the thread, but within that same period and a "rebel" in his own right.

Oops, apologies for missing the Herzen ref before. This is a fascinating topic but I'm afraid I bring more appetite than knowledge to it--looking forward to what everyone unearths.

Just a quick warning I forgot yesterday, not being in the habit of reading e-books myself--in case anyone finds Solovyov and Berdyaev online, perhaps it's not amiss to make sure the website is a known public database or academic resource.

As cornerstone thinkers of the Russian right, it's not unusual to see neonazi sites peddling their texts in pamphlet form etc.

And, just so I don't leave the impression they speak only to the right, it must be noted that their Great-Russian nationalism and Russian-Orthodox messianism is widespread, really popular (even beyond Russia...)

I may find it hard to resist a title like The Life of a Useless Man

Hey, if you do, I'll join you on that. Had the same reaction for ages. :)

>27 thorold:

Have you read Mikhail Kuzmin? Not a revolutionary in the conventional sense so not a great fit to the thread, but within that same period and a "rebel" in his own right.

30thorold

>29 LolaWalser: I didn’t know about Kuzmin — sounds interesting!

There seem to be one or two recordings of his music around: I liked the little bit of the Alexandrian Songs I listened to, I’ll certainly come back to that.

There seem to be one or two recordings of his music around: I liked the little bit of the Alexandrian Songs I listened to, I’ll certainly come back to that.

31SassyLassy

>29 LolaWalser: Not a revolutionary in the conventional sense so not a great fit to the thread

There are at least two sides to every revolution, so read as many as possible, or more likely, as many as you can tolerate!

>29 LolaWalser: >30 thorold: How did I miss this, the Kuzmin Collection at Dalhousie University:

https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/21661/toc_e.html

There are at least two sides to every revolution, so read as many as possible, or more likely, as many as you can tolerate!

>29 LolaWalser: >30 thorold: How did I miss this, the Kuzmin Collection at Dalhousie University:

https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/21661/toc_e.html

32rocketjk

I read Gorky's Bystander way back in 2008. It is long and slow, but in the end I felt like it painted an effective picture of the Russian gentry class in decline, 1880 through around 1905. My full review is on the book's work page. As I put it then, "And yet, as one reads, if one pushes through, an increasingly detailed picture of the ideas and behaviors of the time and place is painted for us. Think of a a very, very long minimalist symphony and you will get the idea."

33SassyLassy

>32 rocketjk: Just read your review, and it sounds as if the book still stands up for a picture of that time.

Have you read The Golovlyov Family? It has the same theme: no balls and ballerinas here, and the gentry is certainly in decline. I think it is one of the most depressing books I have read, and that's probably saying a lot. I think it moves faster than Bystander though, given your description.

Have you read The Golovlyov Family? It has the same theme: no balls and ballerinas here, and the gentry is certainly in decline. I think it is one of the most depressing books I have read, and that's probably saying a lot. I think it moves faster than Bystander though, given your description.

34rocketjk

>34 rocketjk: No, I haven't read the Golovlyov Family, although I remember being it on the shelves of the used bookstore I used to own. Funny how certain covers stick with me.

35thorold

>26 SassyLassy: >27 thorold: Challenge accepted, warm-up exercise done!

Russian thinkers (1978) by Isaiah Berlin (Russia, UK, 1909-1997)

A classic collection of Berlin's essays on nineteenth-century Russian writers, which has suffered a bit from being too much on student reading-lists: the current Penguin edition has expanded so far that the poor little text is almost completely swallowed up in notes and editorial material. But it is worth fighting your way in thought the thickets of forewords and glossaries to get to grips with Berlin's alarmingly concise summaries of what was important in Russian intellectual life, and how the currents of European thought and the concrete events of Russian history influenced the way it developed.

Berlin's big idea, of course, is his repugnance, developed out of his experience of the first half of the 20th century in Europe, for any idea of history or politics that is founded on aggregated utilitarian principles of a common good, or on some sort of promise of future good in exchange for present sacrifice. The primacy of the rights of the individual is always central for him, and that comes through in his choice of heroes: he approves of the social thinker Alexander Herzen and the critic Vissarion Belinsky, who were always ready to dismiss an abstract idea if they didn't like it, but doesn't have much time for dogmatic opportunists like Lenin and Bakunin. Similarly, in literature his preference is for Tolstoy and Turgenev, who let their human characters drive the stories, even if it comes at the expense of the theories they are trying to promote. Poor old Dostoyevsky doesn't even get an essay to himself, although Berlin does approve of the fact that he was arrested for reading out Belinsky's "Letter to Gogol".

I loved Berlin's self-confident, offhand put-downs of things he doesn't like — for instance when he compares the Russian reception of Turgenev's A sportsman's sketches to that in America of Uncle Tom's cabin "from which it differed principally in being a work of genius". He's a critic who bores down to the essentials with great precision, but also someone who doesn't mind telling us about the simple pleasure he takes in a text.

Slightly tough going, and written from a very clear political standpoint, but it makes for a useful overview of who was who: I'll probably come back to it when I've read more Russians.

(I read this in the Penguin edition as a Kobo e-book, which had all sorts of odd formatting errors, most bizarrely the way that all the acute accents in French quotations got turned into grave accents: "èmigrè" — do publishers never read the books they produce?)

Russian thinkers (1978) by Isaiah Berlin (Russia, UK, 1909-1997)

A classic collection of Berlin's essays on nineteenth-century Russian writers, which has suffered a bit from being too much on student reading-lists: the current Penguin edition has expanded so far that the poor little text is almost completely swallowed up in notes and editorial material. But it is worth fighting your way in thought the thickets of forewords and glossaries to get to grips with Berlin's alarmingly concise summaries of what was important in Russian intellectual life, and how the currents of European thought and the concrete events of Russian history influenced the way it developed.

Berlin's big idea, of course, is his repugnance, developed out of his experience of the first half of the 20th century in Europe, for any idea of history or politics that is founded on aggregated utilitarian principles of a common good, or on some sort of promise of future good in exchange for present sacrifice. The primacy of the rights of the individual is always central for him, and that comes through in his choice of heroes: he approves of the social thinker Alexander Herzen and the critic Vissarion Belinsky, who were always ready to dismiss an abstract idea if they didn't like it, but doesn't have much time for dogmatic opportunists like Lenin and Bakunin. Similarly, in literature his preference is for Tolstoy and Turgenev, who let their human characters drive the stories, even if it comes at the expense of the theories they are trying to promote. Poor old Dostoyevsky doesn't even get an essay to himself, although Berlin does approve of the fact that he was arrested for reading out Belinsky's "Letter to Gogol".

I loved Berlin's self-confident, offhand put-downs of things he doesn't like — for instance when he compares the Russian reception of Turgenev's A sportsman's sketches to that in America of Uncle Tom's cabin "from which it differed principally in being a work of genius". He's a critic who bores down to the essentials with great precision, but also someone who doesn't mind telling us about the simple pleasure he takes in a text.

Slightly tough going, and written from a very clear political standpoint, but it makes for a useful overview of who was who: I'll probably come back to it when I've read more Russians.

(I read this in the Penguin edition as a Kobo e-book, which had all sorts of odd formatting errors, most bizarrely the way that all the acute accents in French quotations got turned into grave accents: "èmigrè" — do publishers never read the books they produce?)

36NinieB

>35 thorold: I don't think publishers read e-books, because they are usually full of annoyances like that. That's why I tend to avoid them unless they are free.

37SassyLassy

Just back from a week away in one of the last spots on earth, right here in Canada, where cell reception and wifi are almost impossible to find, especially in weather. I did pass a pole that had a poster on it saying 'wifi hotspot', a new way of connecting.

>35 thorold: Well done - You make me think I should take this on again, this time without an exam at the end!

I always want to read Michael Ignatieff's biography of him too, but somehow have not.

Here are some of his thoughts on Berlin:

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1997/12/18/on-isaiah-berlin-1909-1997/

Getting a weird garbled version of 'enigma' when I try to pronounce 'èmigrè'

>35 thorold: Well done - You make me think I should take this on again, this time without an exam at the end!

I always want to read Michael Ignatieff's biography of him too, but somehow have not.

Here are some of his thoughts on Berlin:

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1997/12/18/on-isaiah-berlin-1909-1997/

Getting a weird garbled version of 'enigma' when I try to pronounce 'èmigrè'

38LolaWalser

I've been meaning to say a few words about this for a long time:

Explodity : sound, image, and word in Russian futurist book art

Revolutionary ferment in Russia was indivisible from the arts, all of them, music to painting to theatre etc. One of the many streams of Russian modernism and avant-garde, dubbed futurism, is most interesting to me for its truly unique nature*. Russian futurists included poets such as Mayakovsky and Velimir Khlebnikov, linguists (Roman Jakobson), painters of Suprematist, neo-Primitive, Constructivist etc. outlook.

Futurist poets were greatly interested in sound, in the phonic quality of speech and its ability to carry meaning--and then past it, going beyond meaning into a "transrational" realm. The combination of sound and image intrigued them no end. They called this poetry zaum (beyond/behind reason, "beyonsense").

The subject of Perloff's monograph is the artistic collaboration in 1910-15 between poets and painters in creation of futurist livres d'artiste, produced in small numbers, by hand, and thus each being completely original.

You can see some of these books and hear this poetry interactively here (translations are included):

http://www.getty.edu/research/publications/explodity/index.html

And at this link, more books, the exhibition (Tango With Cows), and video of the Explodity performance:

http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/tango_with_cows/

*Russian futurism has nothing in common with the Italian futurism, they are so much about different things that straight comparisons of their respective aesthetics are un-illuminating of either. However, one simple opposition that is meaningful can be seen in the Russian futurists' overwhelmingly provincial origins, whereas the Italians were largely metropolitans. Thus, the Russians maintain a great interest in nature as well as in folk art, which they explore for its intuitive qualities, its closeness to primary experiences, whereas the Italians show zero interest in those and are wholly turned to the urban experience.

Politically, Russian futurists were of the left, in stark contrast to the essentially fascist, i.e. extreme right-wing orientation of Italian futurism.

Explodity : sound, image, and word in Russian futurist book art

Revolutionary ferment in Russia was indivisible from the arts, all of them, music to painting to theatre etc. One of the many streams of Russian modernism and avant-garde, dubbed futurism, is most interesting to me for its truly unique nature*. Russian futurists included poets such as Mayakovsky and Velimir Khlebnikov, linguists (Roman Jakobson), painters of Suprematist, neo-Primitive, Constructivist etc. outlook.

Futurist poets were greatly interested in sound, in the phonic quality of speech and its ability to carry meaning--and then past it, going beyond meaning into a "transrational" realm. The combination of sound and image intrigued them no end. They called this poetry zaum (beyond/behind reason, "beyonsense").

The subject of Perloff's monograph is the artistic collaboration in 1910-15 between poets and painters in creation of futurist livres d'artiste, produced in small numbers, by hand, and thus each being completely original.

You can see some of these books and hear this poetry interactively here (translations are included):

http://www.getty.edu/research/publications/explodity/index.html

And at this link, more books, the exhibition (Tango With Cows), and video of the Explodity performance:

http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/tango_with_cows/

*Russian futurism has nothing in common with the Italian futurism, they are so much about different things that straight comparisons of their respective aesthetics are un-illuminating of either. However, one simple opposition that is meaningful can be seen in the Russian futurists' overwhelmingly provincial origins, whereas the Italians were largely metropolitans. Thus, the Russians maintain a great interest in nature as well as in folk art, which they explore for its intuitive qualities, its closeness to primary experiences, whereas the Italians show zero interest in those and are wholly turned to the urban experience.

Politically, Russian futurists were of the left, in stark contrast to the essentially fascist, i.e. extreme right-wing orientation of Italian futurism.

39spiralsheep

>38 LolaWalser: I'm still reading Marc Chagall's autobiography My Life, but I can confirm that one of the cultural trends he emphasises in the 1906-1914 sections is the ideological separation of Russian artistic movements from Parisian movements, even when they appear superficially similar.

He also mentions the influence of Ballets Russes which demonstrated as LolaWalser says, "the Russians maintain a great interest in nature as well as in folk art, which they explore for its intuitive qualities, its closeness to primary experiences".

He also mentions the influence of Ballets Russes which demonstrated as LolaWalser says, "the Russians maintain a great interest in nature as well as in folk art, which they explore for its intuitive qualities, its closeness to primary experiences".

40LolaWalser

>39 spiralsheep:

Note that I was talking specifically about Russian futurists, not the Russian arts scene in general. Chagall was another provincial, but there were plenty of Russian artists and writers in the high literary circles in St. Petersburg and Moscow well acquainted with the European trends and traditions, some of whom felt closer to them than to the native developments. "Classical" modernists like Akhmatova and Mandelstam, Blok and Gumilyov, erudite polyglots, might mingle and perform along with the futurists in the Stray Dog Cabaret and similar venues but they were on different wavelengths (not to mention the reactionaries, the decadents, mystics, symbolists etc.)

Dhiaghileff exoticised his own (or, nominally his own) culture for Western consumption, it's got nothing to do with the interests of the futurists--mind you, he did employ them from time to time--Goncharova most notably. However, that decorative commercial work has little in common with her free experimentation in the futurist art books in the links above.

Note that I was talking specifically about Russian futurists, not the Russian arts scene in general. Chagall was another provincial, but there were plenty of Russian artists and writers in the high literary circles in St. Petersburg and Moscow well acquainted with the European trends and traditions, some of whom felt closer to them than to the native developments. "Classical" modernists like Akhmatova and Mandelstam, Blok and Gumilyov, erudite polyglots, might mingle and perform along with the futurists in the Stray Dog Cabaret and similar venues but they were on different wavelengths (not to mention the reactionaries, the decadents, mystics, symbolists etc.)

Dhiaghileff exoticised his own (or, nominally his own) culture for Western consumption, it's got nothing to do with the interests of the futurists--mind you, he did employ them from time to time--Goncharova most notably. However, that decorative commercial work has little in common with her free experimentation in the futurist art books in the links above.

41Tess_W

Hello! I've lurked for a couple of years, but now that I'm retired I would like to read along, when able. I especially love Tolstoy and have 2 on my shelf: Master and Man and The Death of Ivan llyich. I also have a book of plays by Chekov that has been collecting dust for 20 years. A dilemma as I only have time for one!

42spiralsheep

>40 LolaWalser: I was agreeing with you by noting more general trends.

43thorold

A Kuzmin selection and the NYRB Stray Dog Café anthology have arrived, so I’m all set...

44spiralsheep

>41 Tess_W: Hello! And welcome. I hope you enjoy whichever selection you read.

45LolaWalser

>42 spiralsheep:

Er, that's confusing me. Apologies if what follows is too much pedantry, I get antsy about lack of clarity. I was pointing out the distinction of the futurists, not to be confused with the agenda of some other (let alone all other) Russian groups. There is no single Russian aesthetic, artistic preoccupation, philosophy etc. and therefore no general trend (the plural makes nonsense of "general", no?)

What the futurists mined in nature and folk traditions is different from various tendencies of "going to the people" (which are also different among themselves). The iconography of folk art, for example, disseminated in popular prints and the practice of this printing itself, fascinated them for its immediacy and power--the eye understands the primitive print like the ear understands the sound, without the burden of the overeducated ratio. This interest is planets away from the mystico-religious and/or conservative and/or chauvinistic and/or folkloric, historical etc. interest many others evince for the same traditions.

The "primitivism" of the futurists, the riotous child-like playfulness and roughness of those books, for example, is inspired by and seeks to emulate that immediacy of communication and freedom of the "unschooled" printers of folk prints, but is not itself either "folkish" or unsophisticated. It is also not "traditional" or backward-looking in the least; they were self-consciously propelling themselves where no art had gone before. The name would be a clue to that!

And to do so they used in part the instrumentarium of folk lore. Which is different from being interested in folk lore, tradition etc. for its own sake, historical continuation, identification etc.

Similar remarks pertain to nature, which interested them not (as in almost every other Western European and Russian group) as the site of non- or anti-urbanity (a site of "purity", "innocence", "authenticity" etc.) but as the matrix of primary relations and insights. They were interested in "what occurs" naturally--for instance, what is the "natural", "unschooled" relation of image and sound, how we "naturally" relate to them.

I don't know if I'm choosing the best details because the ground for confusion can be so vast--suffice it to say, one should not mistake the willful "naiveté" of the futurists and the crudeness of their art for some actual lack of sophisticated skill. Their hailing from the provinces only means that they were not originally participants in the usual career of a metropolitan artist; being predominantly middle-to-lower class explains why they wouldn't have knowledge of other languages (and thus of the mostly untranslated foreign literature). But by no means were they uneducated and unskilled.

Khlebnikov, for instance, grew up in a Siberian steppe among Mongolian nomads, but his parents were people of wide culture, his father a scientist, and Khlebnikov would develop his unprecedented poetic experiments from a scientific interest in bird song and other sounds occurring in nature.

Ack, too long.

>43 thorold:

Speaking of, you'll find Kuzmin rubbed elbows with the futurists too!

Er, that's confusing me. Apologies if what follows is too much pedantry, I get antsy about lack of clarity. I was pointing out the distinction of the futurists, not to be confused with the agenda of some other (let alone all other) Russian groups. There is no single Russian aesthetic, artistic preoccupation, philosophy etc. and therefore no general trend (the plural makes nonsense of "general", no?)

What the futurists mined in nature and folk traditions is different from various tendencies of "going to the people" (which are also different among themselves). The iconography of folk art, for example, disseminated in popular prints and the practice of this printing itself, fascinated them for its immediacy and power--the eye understands the primitive print like the ear understands the sound, without the burden of the overeducated ratio. This interest is planets away from the mystico-religious and/or conservative and/or chauvinistic and/or folkloric, historical etc. interest many others evince for the same traditions.

The "primitivism" of the futurists, the riotous child-like playfulness and roughness of those books, for example, is inspired by and seeks to emulate that immediacy of communication and freedom of the "unschooled" printers of folk prints, but is not itself either "folkish" or unsophisticated. It is also not "traditional" or backward-looking in the least; they were self-consciously propelling themselves where no art had gone before. The name would be a clue to that!

And to do so they used in part the instrumentarium of folk lore. Which is different from being interested in folk lore, tradition etc. for its own sake, historical continuation, identification etc.

Similar remarks pertain to nature, which interested them not (as in almost every other Western European and Russian group) as the site of non- or anti-urbanity (a site of "purity", "innocence", "authenticity" etc.) but as the matrix of primary relations and insights. They were interested in "what occurs" naturally--for instance, what is the "natural", "unschooled" relation of image and sound, how we "naturally" relate to them.

I don't know if I'm choosing the best details because the ground for confusion can be so vast--suffice it to say, one should not mistake the willful "naiveté" of the futurists and the crudeness of their art for some actual lack of sophisticated skill. Their hailing from the provinces only means that they were not originally participants in the usual career of a metropolitan artist; being predominantly middle-to-lower class explains why they wouldn't have knowledge of other languages (and thus of the mostly untranslated foreign literature). But by no means were they uneducated and unskilled.

Khlebnikov, for instance, grew up in a Siberian steppe among Mongolian nomads, but his parents were people of wide culture, his father a scientist, and Khlebnikov would develop his unprecedented poetic experiments from a scientific interest in bird song and other sounds occurring in nature.

Ack, too long.

>43 thorold:

Speaking of, you'll find Kuzmin rubbed elbows with the futurists too!

46spiralsheep

Long comment is long. No apologies. :-)

I read My Life by Marc Chagall as part of my recent focus on Belarus.

This autobiography was written by Marc Chagall while he was in Moscow in 1922 when he was in his mid-thirties. It covers his early years in Vitebsk in Belarus in what was then the Russian Empire, his time as a young artist in St Petersburg and Paris, and his return to revolutionary Russia as a mature artist and teacher. Chagall was a secular Jew but his origins in Russian-Jewish folk culture and his beloved hometown of Vitebsk were important to him (and illustrating his wife Bella's book Burning Lights about her childhood in Vitebsk could be said to be a true expression of his own Hasidic, Chabad, upbringing). The expressionistic writing style of this autobiography is very reminiscent of his visual artistic style, which is also amply demonstrated through his many illustrations of the text.

Chagall's account of the Russian Empire and subsequent revolutions (plural) is that of an artist whose interest is in cultural expression not political expression but his account appears to be historically accurate, albeit from a fragmented personal perspective.

1887 onwards - His expressions about his childhood are sharp-eyed to the socio-economic conditions around him but he describes these through lived experience. He loves Vitebsk.

- He notes the ongoing pogroms, targeted murders of Jews, tacitly sanctioned by the Russian Empire, but they are outside his personal experience.

- He notes that Jews are required to perform military service for the Russian Empire (while the Empire criminalises their existence).

- He is honest about receiving state and private patronage which enables him to become a career artist.

1907 - He records his arrest and imprisonment by the Russian Empire for the "crime" of being Jewish in St Petersburg outside the concentration area of the Pale of Settlement.

1914 - He experiences a pogrom consisting of a group of off duty Russian Imperial soldiers murdering Jews on the streets of St Petersburg. He lies about his identity and runs away.

- He is so angry about conscripted Jewish soldiers being deliberately targeted and murdered in pogroms by the Russian Imperial Army that for the first time in 130 pages he names and blames an individual he holds responsible for enabling this murderous anti-Semitism: GD Nicholas Nicolaevich. (I'll add a historical note that Nicholas Nicolaevich also promoted and enacted the genocidal mass murder of German-speaking Russians, Poles, and Muslims, before dying at the age of 72 while living in luxurious exile in France.)

Before the February Revolution 1917 - Chagall deserts his conscripted military post in an office under his brother-in-law's command.

- He is in favour of everyone having a right to life and food. This is humanitarian not political.

After the February Revolution 1917 - He is offered a semi-political position as a national visual art Commissar. He prefers to found and head a regional government art school in Vitebsk (there are some implied minor shenanigans in which he uses state money designated for training artists to feed young men, mostly Jewish, and uses his influence to try to have the same young men exempted from compulsory military service on the grounds that they're training as artists, but obviously he's not entirely candid about this). This school, Vitebsk Art School, became one of the most prominent in Soviet Russia.

After the October Revolution 1917 - He realises the Leninist communists are in the ascendent when the font used on political posters changes.

- A statue of Karl Marx, who Chagall notes was Jewish, is erected in Vitebsk, possibly by sometime art students of Chagall, and then a second statue. Chagall's reaction is to lament the heavy realist style of the sculpture.

- He describes a difficult relationship with Anatoly Lunacharsky the Commissar for Education and says he was threatened with prison because he didn't "at least bow to his (Lunacharsky's) authority". (Side note: in 1919 the right-wing New York Times described Soviet educational reforms, of which Chagall's Vitebsk Art School and his teaching of orphans was a part, in an article headlined, "REDS ARE RUINING CHILDREN OF RUSSIA; Lunacharsky's System of Calculated Moral Depravity Described", lol. Odd for a newspaper to be against increased general literacy... or feeding and housing orphans.)