thorold is hoping to fall even further back in Q4

DiscussãoClub Read 2020

Aderi ao LibraryThing para poder publicar.

1thorold

Welcome to my autumn reading thread! You can find the previous thread here: https://www.librarything.com/topic/321969

2thorold

I seem to have been eating a lot of pumpkins lately, so a pumpkin-related poem:

(Nicander, 2nd century bc — quoted in The Faber book of useful verse, edited by Simon Brett, no translator mentioned)

Those vegans have been around for a while, it seems!

First cut the gourds in slices, and then run

Threads through their breadth, and dry them in the air;

Then smoke them hanging them above the fire;

So that the slaves may in the winter season

Take a large dish and fill it with the slices,

And feast on them on holidays: meanwhile

Let the cook add all sorts of vegetables,

And throw them seed and all into the dish;

Let them take strings of gherkins fairly wash’d,

And mushrooms, and all sorts of herbs in bunches,

And curly cabbages, and add them too.

(Nicander, 2nd century bc — quoted in The Faber book of useful verse, edited by Simon Brett, no translator mentioned)

Those vegans have been around for a while, it seems!

3thorold

Q3 stats:

I finished 62 books in Q3 (70 in Q1, 89 in Q2). A more normal total than the lockdown-inflated Q1 and Q2.

Author gender: M 36, F 26: 58% M ( Q1: 71% M; Q2: 69% M)

Language: EN 42, NL 5, DE 10, FR 2, ES 3 : 68% EN (Q1 54% EN; Q2 78% EN) — still more English than usual

15 books (24%) were linked to the "travelling the TBR" theme read, and 7 (11%) were leftovers from Q2's Southern Africa theme (Q1: 28% "far right" theme; Q2 38% Southern Africa)

Publication dates from 1781 to 2020, mean 1957, median 1976; 4 books were published in the last five years.

Formats: library 0, physical books from the TBR 43, physical books from the main shelves (re-reads) 6, audiobooks 1, paid ebooks 5, other free/borrowed 7 — 69% from the TBR (Q1: 17% from the TBR, Q2: 61%)

Formats: library 0, physical books from the TBR 39, physical books from the main shelves (re-reads) 6, audiobooks 1, paid ebooks 5, other free/borrowed 11 — 63% from the TBR (Q1: 17% from the TBR, Q2: 61%)

47 unique first authors (1.31 books/author; Q1 1.11; Q2 1.15)

By gender: M 30, F 17 : 64% M (Q1 71% M ; Q2 71% M)

By main country: UK 15, NL 5, US 2, FR 3, DE 1, DDR 2, ES 2, AU 3, AR 2 and ZA 8

TBR pile evolution:

22/12/2019 : 105 books (123090 book-days)

31/3/2020 : 110 books (129788 book-days) (Change: 14 read, 19 added)

30/6/2020 : 94 books (102188 book-days) (Change: 54 read, 48 added)

30/9/2020 : 94 books (89465 book-days) (Change: 39 read, 39 added)

There's still plenty of "freshening" going on in the TBR, but mostly at the top: the average days-per-book of what's still there on the pile is 951 days, only a small reduction from Q2. 73 of the 94 books currently on the TBR were already there at the start of Q3, so around half the books I read from the pile must have been short-stay residents.

Correction 11/10/2020: I noticed that when I first posted these numbers, I wrongly counted the Schiller plays as being off the TBR — in fact they all came from the same TBR item, a Complete Works, but I've been making dummy catalogue entries for each play in the "Read but unowned" category so that I could post separate reviews. That means the true number of books leaving the TBR was 39, not 43 as I originally said.

I finished 62 books in Q3 (70 in Q1, 89 in Q2). A more normal total than the lockdown-inflated Q1 and Q2.

Author gender: M 36, F 26: 58% M ( Q1: 71% M; Q2: 69% M)

Language: EN 42, NL 5, DE 10, FR 2, ES 3 : 68% EN (Q1 54% EN; Q2 78% EN) — still more English than usual

15 books (24%) were linked to the "travelling the TBR" theme read, and 7 (11%) were leftovers from Q2's Southern Africa theme (Q1: 28% "far right" theme; Q2 38% Southern Africa)

Publication dates from 1781 to 2020, mean 1957, median 1976; 4 books were published in the last five years.

Formats: library 0, physical books from the TBR 39, physical books from the main shelves (re-reads) 6, audiobooks 1, paid ebooks 5, other free/borrowed 11 — 63% from the TBR (Q1: 17% from the TBR, Q2: 61%)

47 unique first authors (1.31 books/author; Q1 1.11; Q2 1.15)

By gender: M 30, F 17 : 64% M (Q1 71% M ; Q2 71% M)

By main country: UK 15, NL 5, US 2, FR 3, DE 1, DDR 2, ES 2, AU 3, AR 2 and ZA 8

TBR pile evolution:

22/12/2019 : 105 books (123090 book-days)

31/3/2020 : 110 books (129788 book-days) (Change: 14 read, 19 added)

30/6/2020 : 94 books (102188 book-days) (Change: 54 read, 48 added)

30/9/2020 : 94 books (89465 book-days) (Change: 39 read, 39 added)

There's still plenty of "freshening" going on in the TBR, but mostly at the top: the average days-per-book of what's still there on the pile is 951 days, only a small reduction from Q2. 73 of the 94 books currently on the TBR were already there at the start of Q3, so around half the books I read from the pile must have been short-stay residents.

Correction 11/10/2020: I noticed that when I first posted these numbers, I wrongly counted the Schiller plays as being off the TBR — in fact they all came from the same TBR item, a Complete Works, but I've been making dummy catalogue entries for each play in the "Read but unowned" category so that I could post separate reviews. That means the true number of books leaving the TBR was 39, not 43 as I originally said.

4thorold

Q3 highlights / Q4 goals

After being quite project-focussed earlier in the year — the Reading Globally theme-reads on the rise of the far-right and on Southern Africa; the last stages of the Zolathon — it was good to release the grip a little in Q3, so there was quite a lot of randomness in my reading over the last three months. I found myself chasing minor connections, like Australian textile fiction (Bobbin up as a follow-on to The dyehouse) and DDR fiction (Die Aula, Das Windhahn-Syndrom), tidying up loose ends from my dip into B S Johnson, and so on.

I finished Q3 partway through two new projects: I'm reading through Schiller's plays at the rate of about one a week — Die Jungfrau von Orleans will be next. And I'm also (re-)reading A S Byatt — I'm reading Babel Tower at the moment. Both of those should keep me busy for a little while longer.

The other big project that is coming up is the next RG Theme Read, on Russians and revolutions.

Books that really stand out in Q3:

- Ali Smith's Summer, the last of the seasonal quartet

- Bessie Head's Serowe, rural oral history with an African flavour

- The bell jar and Possession — both books I thought I knew too well to need to re-read!

- Thomas Bernhard's collected poems

After being quite project-focussed earlier in the year — the Reading Globally theme-reads on the rise of the far-right and on Southern Africa; the last stages of the Zolathon — it was good to release the grip a little in Q3, so there was quite a lot of randomness in my reading over the last three months. I found myself chasing minor connections, like Australian textile fiction (Bobbin up as a follow-on to The dyehouse) and DDR fiction (Die Aula, Das Windhahn-Syndrom), tidying up loose ends from my dip into B S Johnson, and so on.

I finished Q3 partway through two new projects: I'm reading through Schiller's plays at the rate of about one a week — Die Jungfrau von Orleans will be next. And I'm also (re-)reading A S Byatt — I'm reading Babel Tower at the moment. Both of those should keep me busy for a little while longer.

The other big project that is coming up is the next RG Theme Read, on Russians and revolutions.

Books that really stand out in Q3:

- Ali Smith's Summer, the last of the seasonal quartet

- Bessie Head's Serowe, rural oral history with an African flavour

- The bell jar and Possession — both books I thought I knew too well to need to re-read!

- Thomas Bernhard's collected poems

5dchaikin

enjoyed this Nicander ode to pumpkins (and slaves!)

I meant to comment in your old thread on Le Clezio's The interrogation. I read it about 5 years ago, and my review concluded, "if you want to try Le Clezio, don't start here." : ) The other books I have read from him have a wonderful flow he doesn't really manage to hint at in this first novel, so, why i can't promise you will like le Clezio as much as I have, I think I can gently suggest you haven't really have that le Clezio experience yet.

I meant to comment in your old thread on Le Clezio's The interrogation. I read it about 5 years ago, and my review concluded, "if you want to try Le Clezio, don't start here." : ) The other books I have read from him have a wonderful flow he doesn't really manage to hint at in this first novel, so, why i can't promise you will like le Clezio as much as I have, I think I can gently suggest you haven't really have that le Clezio experience yet.

6avaland

>1 thorold: Lovely photo!

>2 thorold: Not terribly impressed with 2nd century poetry;-) By those standards Julia Child would be a master! (and slaves!)

>4 thorold: "Australian textile fiction" ...is that a thing? I might be interested in those reads. Hmmmm,

>2 thorold: Not terribly impressed with 2nd century poetry;-) By those standards Julia Child would be a master! (and slaves!)

>4 thorold: "Australian textile fiction" ...is that a thing? I might be interested in those reads. Hmmmm,

7thorold

>5 dchaikin: Yes, I’m reserving judgement on Le Clézio — I’ve still got The prospector lined up on the TBR anyway. There was a lot I liked in Le procés-verbal, that probably didn’t come across in my review, but it’s not an easy book to take in.

>6 avaland: As a recipe it’s a bit light on detail, and as a poem it’s a bit light on poetry — maybe it was better in Greek. In his defence, Nicander was the gardening correspondent (and a physician by training, it seems), he wasn’t writing the cookery column. And the poem this is taken from survives only in fragments quoted by other writers.

I don’t think it is a thing really, I just happen to have read two in close succession! If you were writing a dissertation you’d probably call it “Australian industrial fiction” — but textiles (wool) were an important part of the economy in Australia in the 50s and 60s, and textile factories are always interesting from a social point of view because they employ a lot of women, so it’s not totally way-out.

>6 avaland: As a recipe it’s a bit light on detail, and as a poem it’s a bit light on poetry — maybe it was better in Greek. In his defence, Nicander was the gardening correspondent (and a physician by training, it seems), he wasn’t writing the cookery column. And the poem this is taken from survives only in fragments quoted by other writers.

I don’t think it is a thing really, I just happen to have read two in close succession! If you were writing a dissertation you’d probably call it “Australian industrial fiction” — but textiles (wool) were an important part of the economy in Australia in the 50s and 60s, and textile factories are always interesting from a social point of view because they employ a lot of women, so it’s not totally way-out.

8thorold

The next re-read in my Byatt cycle: another big hefty full-scale novel (or two interleaved ones, depending on how you look at it...) after the two elegant little collections of short pieces. It's hard to believe that it's more than 20 years since this one came out, it still feels to me like a very recent book:

Babel Tower (1996) by A S Byatt (UK, 1936- )

The third in the Frederica saga: we're now in the mid-sixties. Frederica's impulsive marriage to Nigel Reiver has not worked out well, and she's trying to build a new life as a literary single parent in London, teaching adult education classes, reviewing, and reading manuscripts for a publisher. Alexander is on a government committee that's reporting on possible reforms of the teaching of English in schools, and Daniel is working for the Samaritans out of a switchboard in a church crypt.

Byatt comments ironically on the challenge-everything ethos of the Swinging Sixties by bringing in a full-scale book-within-a-book, Babbletower, a fantasy novel set in a libertine community where the do-what-thou-wilt ideals of Sade and Fourier are taken to their grotesque, horrific conclusion.

The book ends in two — parallel — extended set-piece court scenes, as Frederica's marriage is ended under the still unreformed divorce laws of the time in one court, and the author and publisher of Babbletower are tried for obscenity in another. We see how clumsy an instrument the legal mechanism for determining truth is when it has to deal with the emotional reality of a marriage or the literary reality of a novel. But we've already seen Frederica trying and failing to resolve her firsthand experience of sex and love with the supposedly authoritative — but mutually conflicting! — understanding she has learnt to look for from her reading of E M Forster and D H Lawrence. And we see that each of the so-called experts who give evidence for and against Babbletower has taken something quite different from the book from what we saw in it as readers, and different again from what the author thought he was putting in.

This is a very big, serious, complicated novel of ideas, but it's also a very funny book, full of mischievous caricatures of sixties types — two dreadful Liverpool Poets, Anthony Burgess (safely dead, and therefore playing himself, hilariously), Angus Wilson (a friend of the author's sister, and therefore disguised slightly), trendy clergymen and trendier psychoanalysts, a Bowie-esque pop star, various artists, a vicar's-wife novelist, etc. Best of all, of course, but a full-scale character rather than a mere caricature, is the author of Babbletower, Jude Mason, who shares a profession and some aspects of his personality with Quentin Crisp, but turns out to have a quite different background.

Oh yes, this is a Byatt novel, so it doesn't stop with one book-within-a-book: as well as Babbletower there is a Tolkienish quest-novel being written as a serial for the children by Frederica's childcare-partner, Agatha Mond, and there is Frederica's own work-in-progress, a collage and cut-up book she calls Laminations. Not to mention the usual literary fun and games with parodies of reviews, novel reports, student essays, and the documents of Alexander's committee. And — just in passing — a lot of serious discussion of the nature of language, the sources of morality, the way these things develop in children, cults, Happenings, charismatic Christianity, ritual, the sexuality of snails, the effects of pesticides, and much more.

A lot to take in, even at a second or third reading. But vastly entertaining.

Babel Tower (1996) by A S Byatt (UK, 1936- )

The third in the Frederica saga: we're now in the mid-sixties. Frederica's impulsive marriage to Nigel Reiver has not worked out well, and she's trying to build a new life as a literary single parent in London, teaching adult education classes, reviewing, and reading manuscripts for a publisher. Alexander is on a government committee that's reporting on possible reforms of the teaching of English in schools, and Daniel is working for the Samaritans out of a switchboard in a church crypt.

Byatt comments ironically on the challenge-everything ethos of the Swinging Sixties by bringing in a full-scale book-within-a-book, Babbletower, a fantasy novel set in a libertine community where the do-what-thou-wilt ideals of Sade and Fourier are taken to their grotesque, horrific conclusion.

The book ends in two — parallel — extended set-piece court scenes, as Frederica's marriage is ended under the still unreformed divorce laws of the time in one court, and the author and publisher of Babbletower are tried for obscenity in another. We see how clumsy an instrument the legal mechanism for determining truth is when it has to deal with the emotional reality of a marriage or the literary reality of a novel. But we've already seen Frederica trying and failing to resolve her firsthand experience of sex and love with the supposedly authoritative — but mutually conflicting! — understanding she has learnt to look for from her reading of E M Forster and D H Lawrence. And we see that each of the so-called experts who give evidence for and against Babbletower has taken something quite different from the book from what we saw in it as readers, and different again from what the author thought he was putting in.

This is a very big, serious, complicated novel of ideas, but it's also a very funny book, full of mischievous caricatures of sixties types — two dreadful Liverpool Poets, Anthony Burgess (safely dead, and therefore playing himself, hilariously), Angus Wilson (a friend of the author's sister, and therefore disguised slightly), trendy clergymen and trendier psychoanalysts, a Bowie-esque pop star, various artists, a vicar's-wife novelist, etc. Best of all, of course, but a full-scale character rather than a mere caricature, is the author of Babbletower, Jude Mason, who shares a profession and some aspects of his personality with Quentin Crisp, but turns out to have a quite different background.

Oh yes, this is a Byatt novel, so it doesn't stop with one book-within-a-book: as well as Babbletower there is a Tolkienish quest-novel being written as a serial for the children by Frederica's childcare-partner, Agatha Mond, and there is Frederica's own work-in-progress, a collage and cut-up book she calls Laminations. Not to mention the usual literary fun and games with parodies of reviews, novel reports, student essays, and the documents of Alexander's committee. And — just in passing — a lot of serious discussion of the nature of language, the sources of morality, the way these things develop in children, cults, Happenings, charismatic Christianity, ritual, the sexuality of snails, the effects of pesticides, and much more.

A lot to take in, even at a second or third reading. But vastly entertaining.

9avaland

>7 thorold: ...textile factories are always interesting from a social point of view... Indeed! Which is why I was interested, although my interest has been 19th & 20th century US textile factories (with a nod to the earlier UK factories).

10thorold

Following on from the fun I had with my multimedia Don Carlos day a few weeks ago, I decided to do something similar with the next Schiller play in my list. This one always gets compared to Shaw's play on the same subject — I don't have a copy of that on my shelves to re-read (and I'm not sure I could face an entire Shaw preface, even on a rainy Sunday afternoon...), but I did find Otto Preminger's film adaptation of it...

Die Jungfrau von Orleans (1801; The Maid of Orleans) by Friedrich Schiller (Germany, 1759-1805)

Saint Joan (1924) by George Bernard Shaw (Ireland, UK, 1856-1950) — 1957 film version adapted by Graham Greene and directed by Otto Preminger

Schiller

Schiller's work on this play in 1800-1801 overlapped with the writing of Maria Stuart. The proposed first performance in Weimar in spring 1801 didn't take place, but it was presented in Leipzig in September of that year, and the text was published a month later.

(Irrelevant fun fact: my edition quotes a letter from Schiller to Körner dated 5 January 1801, where he talks about his progress with the play and says he has "closed the old century productively". None of this innumerate nonsense we had twenty years ago when people thought the century ended in December '99!)

Maybe it wasn't a good idea writing two plays about tragic female figures, one "bad" and one "good", close together: Schiller seems to have struggled with the construction of this play, and put a lot of effort into researching the trial scenes before deciding to abandon them altogether and revise history slightly(!) by having Joan escape from English captivity and die gloriously on the battlefield.

Schiller's Joan, as we might expect, is a romantic-nationalist heroine, a young rebel whose business is to knock heads together on the battlefield as well as in the conference room to encourage the leaders of France and Burgundy to forget their petty local quarrels and unite to drive out the foreign occupying army. Any resemblance to the situation in Germany in 1801 is purely coincidental! Religion doesn't play a very large part in Schiller's presentation of the story: Joan uses religious language, of course, but the French and English leaders all, rather implausibly, seem to be children of the age of Voltaire, supremely cynical about Christian belief.

There's an interesting little bit in III:iv, which raises a few little questions about historical determinism, free-will, prophecy, and hindsight: Joan prophesies to the newly-crowned Dauphin (now Charles VII) that his descendants will be glorious kings — but only until the French Revolution:

Joan is more like one of Schiller's impetuous young men (Posa, in particular) than any of his women, although he does make the tragedy pivot on her sexuality: The moment when Joan feels a brief sexual attraction to an English knight she's about to kill in battle is the moment when she starts to lose her absolute certainty in the divine origin of her mission to unite France, and the moment when she becomes vulnerable to the accusation of witchcraft — which comes, interestingly, not from the Church or the political establishment, but from her father. Schiller clearly doesn't approve of fathers. (The Dauphin, of course, also had a somewhat problematic father...).

This is really a one-girl play. The men, led by the Dauphin and Dunois (the Bastard) all have relatively minor parts; the Dauphin's mother, Isabeau of Bavaria, gets a nice, if not very extensive, bad-girl part, while his mistress, Agnes Sorel, is presented more sympathetically, but also doesn't get a huge amount to do.

Shaw / Greene / Preminger

If Shaw's St Joan isn't quite — as T S Eliot once suggested — an imprisoned Suffragette, she is certainly a graduate of Newnham or Somerville, a clever young woman who has been brought up to wear Rational Dress and dispense gratuitous advice to ignorant, prejudiced and stupid men. And she's not so much a nationalist hero as a victim of cynical English imperialism and the Catholic hierarchy. However, Shaw is a lot more conscientious than Schiller about staying within the limits of recorded history: he twists the way people say things, but not what happens.

Preminger's film cuts the length of the play by about 30%, and by getting Graham Greene to do the screenplay he made sure that it would shift the emphasis from politics to religion: we lose all the stuff about the Burgundians and Isabeau, but see more of Joan's — reported — miracle-working, and the way the church responds to it. Shaw also builds up the Dauphin into a more unconventional character than Schiller does: he's a modern young man who would far rather play hopscotch than be anointed with smelly old holy oil, and he's quite happy to let others run the country.

The thing that Preminger was most heavily criticised for at the time was his casting (through a heavily publicised talent competition) of the inexperienced teenager Jean Seberg in the main part. It's all too obvious when she's working with a bunch of sophisticated, pre-war stage actors that she doesn't know what to do with her body or her voice, and half the time she looks absolutely petrified. Sixty years later, that turns out to be the most charming thing about the film: she's beautiful, vulnerable, and her gaucherie is entirely in character anyway, taking the dated Oxbridge/Major Barbara element out of Shaw's dialogue. It's the mannered, theatrical acting of the old guys that dates the film...

Of course, there's a lot of nonsense in the film: business with horses and suits of armour that make you think of Monty Python, Charles VII processing out of Reims cathedral to the tune of a Handelian fugue, bits of Shaw's dialogue that now strike us as awkwardly anachronistic, weird mixes of location shots and painted back scenes, and so on. But it is quite fun, and the storytelling is nice and tight. Greene knew where to cut.

---

Bonus disc: not part of my multimedia adventure, but something else on the same subject I saw a couple of years ago

Jeannette, l'enfance de Jeanne d'Arc (2017) directed by Bruno Dumont

A totally silly film, when set against the seriousness of Schiller, Shaw and Preminger — Dumont for some reason decided to make an ironic rock-musical adaptation of a couple of pious late-19th-century plays for children by Charles Péguy. Jeanne is portrayed as a very ordinary unwashed small peasant girl in bare feet and a ragged dress, sitting on a heath in the middle of her sheep and goats, speaking Péguy's ridiculously high-flown dialogue like a Sunday-school pupil forced to learn the main part in a play she never wanted to be in. And from time to time she breaks into song-and-dance sequences accompanied by a heavy-metal soundtrack. The goats are magnificent, but it all goes on for far too long, as such things usually do.

I haven't seen the sequel Jeanne (2019), but it sounds as though that continues in the same spirit.

Die Jungfrau von Orleans (1801; The Maid of Orleans) by Friedrich Schiller (Germany, 1759-1805)

Saint Joan (1924) by George Bernard Shaw (Ireland, UK, 1856-1950) — 1957 film version adapted by Graham Greene and directed by Otto Preminger

Schiller

Schiller's work on this play in 1800-1801 overlapped with the writing of Maria Stuart. The proposed first performance in Weimar in spring 1801 didn't take place, but it was presented in Leipzig in September of that year, and the text was published a month later.

(Irrelevant fun fact: my edition quotes a letter from Schiller to Körner dated 5 January 1801, where he talks about his progress with the play and says he has "closed the old century productively". None of this innumerate nonsense we had twenty years ago when people thought the century ended in December '99!)

Maybe it wasn't a good idea writing two plays about tragic female figures, one "bad" and one "good", close together: Schiller seems to have struggled with the construction of this play, and put a lot of effort into researching the trial scenes before deciding to abandon them altogether and revise history slightly(!) by having Joan escape from English captivity and die gloriously on the battlefield.

Schiller's Joan, as we might expect, is a romantic-nationalist heroine, a young rebel whose business is to knock heads together on the battlefield as well as in the conference room to encourage the leaders of France and Burgundy to forget their petty local quarrels and unite to drive out the foreign occupying army. Any resemblance to the situation in Germany in 1801 is purely coincidental! Religion doesn't play a very large part in Schiller's presentation of the story: Joan uses religious language, of course, but the French and English leaders all, rather implausibly, seem to be children of the age of Voltaire, supremely cynical about Christian belief.

There's an interesting little bit in III:iv, which raises a few little questions about historical determinism, free-will, prophecy, and hindsight: Joan prophesies to the newly-crowned Dauphin (now Charles VII) that his descendants will be glorious kings — but only until the French Revolution:

Dein Stamm wird blühn, solang er sich die Liebe

Bewahrt im Herzen seines Volks,

Der Hochmut nur kann ihn zum Falle führen,

Und von den niedern Hütten, wo dir jetzt

Der Retter ausging, droht geheimnisvoll

Den schuldbefleckten Enkeln das Verderben!

Joan is more like one of Schiller's impetuous young men (Posa, in particular) than any of his women, although he does make the tragedy pivot on her sexuality: The moment when Joan feels a brief sexual attraction to an English knight she's about to kill in battle is the moment when she starts to lose her absolute certainty in the divine origin of her mission to unite France, and the moment when she becomes vulnerable to the accusation of witchcraft — which comes, interestingly, not from the Church or the political establishment, but from her father. Schiller clearly doesn't approve of fathers. (The Dauphin, of course, also had a somewhat problematic father...).

This is really a one-girl play. The men, led by the Dauphin and Dunois (the Bastard) all have relatively minor parts; the Dauphin's mother, Isabeau of Bavaria, gets a nice, if not very extensive, bad-girl part, while his mistress, Agnes Sorel, is presented more sympathetically, but also doesn't get a huge amount to do.

Shaw / Greene / Preminger

If Shaw's St Joan isn't quite — as T S Eliot once suggested — an imprisoned Suffragette, she is certainly a graduate of Newnham or Somerville, a clever young woman who has been brought up to wear Rational Dress and dispense gratuitous advice to ignorant, prejudiced and stupid men. And she's not so much a nationalist hero as a victim of cynical English imperialism and the Catholic hierarchy. However, Shaw is a lot more conscientious than Schiller about staying within the limits of recorded history: he twists the way people say things, but not what happens.

Preminger's film cuts the length of the play by about 30%, and by getting Graham Greene to do the screenplay he made sure that it would shift the emphasis from politics to religion: we lose all the stuff about the Burgundians and Isabeau, but see more of Joan's — reported — miracle-working, and the way the church responds to it. Shaw also builds up the Dauphin into a more unconventional character than Schiller does: he's a modern young man who would far rather play hopscotch than be anointed with smelly old holy oil, and he's quite happy to let others run the country.

The thing that Preminger was most heavily criticised for at the time was his casting (through a heavily publicised talent competition) of the inexperienced teenager Jean Seberg in the main part. It's all too obvious when she's working with a bunch of sophisticated, pre-war stage actors that she doesn't know what to do with her body or her voice, and half the time she looks absolutely petrified. Sixty years later, that turns out to be the most charming thing about the film: she's beautiful, vulnerable, and her gaucherie is entirely in character anyway, taking the dated Oxbridge/Major Barbara element out of Shaw's dialogue. It's the mannered, theatrical acting of the old guys that dates the film...

Of course, there's a lot of nonsense in the film: business with horses and suits of armour that make you think of Monty Python, Charles VII processing out of Reims cathedral to the tune of a Handelian fugue, bits of Shaw's dialogue that now strike us as awkwardly anachronistic, weird mixes of location shots and painted back scenes, and so on. But it is quite fun, and the storytelling is nice and tight. Greene knew where to cut.

---

Bonus disc: not part of my multimedia adventure, but something else on the same subject I saw a couple of years ago

Jeannette, l'enfance de Jeanne d'Arc (2017) directed by Bruno Dumont

A totally silly film, when set against the seriousness of Schiller, Shaw and Preminger — Dumont for some reason decided to make an ironic rock-musical adaptation of a couple of pious late-19th-century plays for children by Charles Péguy. Jeanne is portrayed as a very ordinary unwashed small peasant girl in bare feet and a ragged dress, sitting on a heath in the middle of her sheep and goats, speaking Péguy's ridiculously high-flown dialogue like a Sunday-school pupil forced to learn the main part in a play she never wanted to be in. And from time to time she breaks into song-and-dance sequences accompanied by a heavy-metal soundtrack. The goats are magnificent, but it all goes on for far too long, as such things usually do.

I haven't seen the sequel Jeanne (2019), but it sounds as though that continues in the same spirit.

11thorold

...and a quick one from the pile. This is another from my little stack of English-language paperbacks published under the Seven Seas Books imprint in East Berlin.

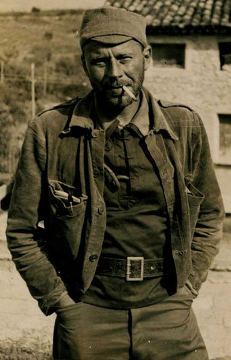

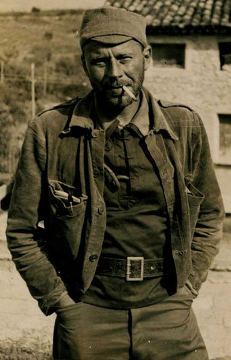

The volunteers (1953; Seven Seas 1958) by Steve Nelson (USA, 1903-1993)

Steve Nelson was an industrial worker who became a union organiser and a prominent figure in the Communist Party of the USA, famous at the time this book appeared as one of the victims of the McCarthy-era witch-hunts. He described that experience in his book The 13th juror, and later also wrote an autobiography Steve Nelson: American radical.

The volunteers is a memoir of Nelson's time with the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. He describes the process of getting into Spain illegally from France and his service as political commissar of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, in action at Brunete and Belchite, amongst other places. The purely military part of the book gives quite a vivid description of what it must have been like actually to fight in the war — a lot of the more literary accounts are by people who didn't see any front-line service — and there are some touching portraits of friends who were killed in action. But he also still seems to be busy with his work as political commissar, so there is a lot of bitterness about the evil Trotskyites, anarchists, syndicalists, socialists and liberals who undermined the unity of the Republican side. Nelson's informal style, full of working-class American idioms of the time, reads a little oddly to start with, but you soon get used to it.

The book comes with a Foreword by Joseph North summarising the circumstances of Nelson's arrest and conviction in 1953 under trumped-up sedition charges — it's notable that when Seven Seas published this book in Eastern Europe in 1958, they conveniently forgot to update it to mention that the charges had been dropped in the meantime, after Nelson took the case to the Supreme Court, or that Nelson had been one of the many people who left the Party in 1956 after the Khrushchev speech and the Soviet intervention in Hungary.

The volunteers (1953; Seven Seas 1958) by Steve Nelson (USA, 1903-1993)

Steve Nelson was an industrial worker who became a union organiser and a prominent figure in the Communist Party of the USA, famous at the time this book appeared as one of the victims of the McCarthy-era witch-hunts. He described that experience in his book The 13th juror, and later also wrote an autobiography Steve Nelson: American radical.

The volunteers is a memoir of Nelson's time with the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. He describes the process of getting into Spain illegally from France and his service as political commissar of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, in action at Brunete and Belchite, amongst other places. The purely military part of the book gives quite a vivid description of what it must have been like actually to fight in the war — a lot of the more literary accounts are by people who didn't see any front-line service — and there are some touching portraits of friends who were killed in action. But he also still seems to be busy with his work as political commissar, so there is a lot of bitterness about the evil Trotskyites, anarchists, syndicalists, socialists and liberals who undermined the unity of the Republican side. Nelson's informal style, full of working-class American idioms of the time, reads a little oddly to start with, but you soon get used to it.

The book comes with a Foreword by Joseph North summarising the circumstances of Nelson's arrest and conviction in 1953 under trumped-up sedition charges — it's notable that when Seven Seas published this book in Eastern Europe in 1958, they conveniently forgot to update it to mention that the charges had been dropped in the meantime, after Nelson took the case to the Supreme Court, or that Nelson had been one of the many people who left the Party in 1956 after the Khrushchev speech and the Soviet intervention in Hungary.

12baswood

Good to follow your return journey through A S Byatt's bibliography. Babel Tower sounds like great fun and one I am adding to my wish list. I have got The Children's Book coming up for a read soon and so I will look forward to your review.

13thorold

>12 baswood: I’ve still got two novels and two short story collections to go before I get to The children’s book! In case you can’t wait, my original review from 2010 is here: https://www.librarything.com/review/55712754 — I didn’t say much at the time, because lots of other people had already posted detailed reviews. There’s lots of interesting stuff there about the Fabians and E. Nesbit.

Babel tower makes most sense if you’ve read the previous two Frederica novels, although you probably can enjoy it without that.

Babel tower makes most sense if you’ve read the previous two Frederica novels, although you probably can enjoy it without that.

14thorold

A warm-up for "Russians write revolutions", read after a little goading from certain RG members...

Russian thinkers (1978) by Isaiah Berlin (Russia, UK, 1909-1997)

A classic collection of Berlin's essays on nineteenth-century Russian writers, which has suffered a bit from being too much on student reading-lists: the current Penguin edition has expanded so far that the poor little text is almost completely swallowed up in notes and editorial material. But it is worth fighting your way in thought the thickets of forewords and glossaries to get to grips with Berlin's alarmingly concise summaries of what was important in Russian intellectual life, and how the currents of European thought and the concrete events of Russian history influenced the way it developed.

Berlin's big idea, of course, is his repugnance, developed out of his experience of the first half of the 20th century in Europe, for any idea of history or politics that is founded on aggregated utilitarian principles of a common good, or on some sort of promise of future good in exchange for present sacrifice. The primacy of the rights of the individual is always central for him, and that comes through in his choice of heroes: he approves of the social thinker Alexander Herzen and the critic Vissarion Belinsky, who were always ready to dismiss an abstract idea if they didn't like it, but doesn't have much time for dogmatic opportunists like Lenin and Bakunin. Similarly, in literature his preference is for Tolstoy and Turgenev, who let their human characters drive the stories, even if it comes at the expense of the theories they are trying to promote. Poor old Dostoyevsky doesn't even get an essay to himself, although Berlin does approve of the fact that he was arrested for reading out Belinsky's "Letter to Gogol".

I loved Berlin's self-confident, offhand put-downs of things he doesn't like — for instance when he compares the Russian reception of Turgenev's A sportsman's sketches to that in America of Uncle Tom's cabin "from which it differed principally in being a work of genius". He's a critic who bores down to the essentials with great precision, but also someone who doesn't mind telling us about the simple pleasure he takes in a text.

Slightly tough going, and written from a very clear political standpoint, but it makes for a useful overview of who was who: I'll probably come back to it when I've read more Russians.

(I read this in the Penguin edition as a Kobo e-book, which had all sorts of odd formatting errors, most bizarrely the way that all the acute accents in French quotations got turned into grave accents: "èmigrè" — do publishers never read the books they produce?)

Russian thinkers (1978) by Isaiah Berlin (Russia, UK, 1909-1997)

A classic collection of Berlin's essays on nineteenth-century Russian writers, which has suffered a bit from being too much on student reading-lists: the current Penguin edition has expanded so far that the poor little text is almost completely swallowed up in notes and editorial material. But it is worth fighting your way in thought the thickets of forewords and glossaries to get to grips with Berlin's alarmingly concise summaries of what was important in Russian intellectual life, and how the currents of European thought and the concrete events of Russian history influenced the way it developed.

Berlin's big idea, of course, is his repugnance, developed out of his experience of the first half of the 20th century in Europe, for any idea of history or politics that is founded on aggregated utilitarian principles of a common good, or on some sort of promise of future good in exchange for present sacrifice. The primacy of the rights of the individual is always central for him, and that comes through in his choice of heroes: he approves of the social thinker Alexander Herzen and the critic Vissarion Belinsky, who were always ready to dismiss an abstract idea if they didn't like it, but doesn't have much time for dogmatic opportunists like Lenin and Bakunin. Similarly, in literature his preference is for Tolstoy and Turgenev, who let their human characters drive the stories, even if it comes at the expense of the theories they are trying to promote. Poor old Dostoyevsky doesn't even get an essay to himself, although Berlin does approve of the fact that he was arrested for reading out Belinsky's "Letter to Gogol".

I loved Berlin's self-confident, offhand put-downs of things he doesn't like — for instance when he compares the Russian reception of Turgenev's A sportsman's sketches to that in America of Uncle Tom's cabin "from which it differed principally in being a work of genius". He's a critic who bores down to the essentials with great precision, but also someone who doesn't mind telling us about the simple pleasure he takes in a text.

Slightly tough going, and written from a very clear political standpoint, but it makes for a useful overview of who was who: I'll probably come back to it when I've read more Russians.

(I read this in the Penguin edition as a Kobo e-book, which had all sorts of odd formatting errors, most bizarrely the way that all the acute accents in French quotations got turned into grave accents: "èmigrè" — do publishers never read the books they produce?)

15thorold

And guess who's back...

A short-story collection I hadn't read before, and a short novel that was a re-read (I posted a review on a previous re-read in 2012, so this is at least the third time I've read it). Both with various familiar threads in Byatt's fiction, but also linked by a new interest in Ibsen and Peer Gynt:

Elementals : stories of fire and ice (1998) by A S Byatt (UK, 1936- )

The biographer's tale (2000) by A S Byatt (UK, 1936- )

Elementals plays around with different aspects of "fire and ice", often also riffing off the idea of Peer Gynt's journey to Africa, especially in "Crocodile Tears" when a Norwegian on the run from a moral failure has a transformative experience in Nîmes, and in "Cold" when an ice-princess journeys to the desert with her fiery glass-blowing husband. "A Lamia in the Cévennes" brings in Keats in an unexpected way (and sent me back to read a poem I haven't looked at for many years) when a painter finds an unexpected sea-serpent in his swimming-pool. And there are some lovely miniatures, as well, especially the Velasquez story "Christ in the House of Jesus and Mary" and "Jael", where a very English film-director looks back on an incident in her early schooldays.

The biographer's tale would be a full-scale novel from anyone else, but by Byatt standards it feels more like an extended novella, with a first-person narrator and only a single plot line. It's great fun, in any case, obviously meant as a slightly tongue-in-cheek penance for the bad press she gave biographers and biography in Possession.

Postgraduate student Phineas G Nanson (*) decides in the middle of a dull seminar that what he cares for are solid facts, and that he doesn't want to become a post-structuralist critic after all. Captivated by an old-fashioned three volume biography of a Victorian polymath, he decides to switch his research topic to the author of the biography, Scholes Destry-Scholes. But this isn't as straightforward as he imagined: Scholes Destry-Scholes turns out to be a very elusive figure, whose traces in the world are teasing, fragmentary and contradictory in a way that he would be forced to call postmodern if he didn't know better. The trail leads him to Carl Linnaeus, Francis Galton and Henrik Ibsen, as well as to the Swedish bee-taxonomist and part-time earth-goddess, Fulla, to Scholes Destry-Scholes's lovely niece Vera, and to a possibly-dubious travel agency called "Puck's Girdle". It's all very confusing, but oddly satisfying, and full of delightfully miscellaneous information about literature, biology and the way they relate — always a core topic for Byatt.

---

(*) Byatt only gives away how she arrived at this rather cryptographic name to those who read the acknowledgements section attentively!

A short-story collection I hadn't read before, and a short novel that was a re-read (I posted a review on a previous re-read in 2012, so this is at least the third time I've read it). Both with various familiar threads in Byatt's fiction, but also linked by a new interest in Ibsen and Peer Gynt:

Elementals : stories of fire and ice (1998) by A S Byatt (UK, 1936- )

The biographer's tale (2000) by A S Byatt (UK, 1936- )

Elementals plays around with different aspects of "fire and ice", often also riffing off the idea of Peer Gynt's journey to Africa, especially in "Crocodile Tears" when a Norwegian on the run from a moral failure has a transformative experience in Nîmes, and in "Cold" when an ice-princess journeys to the desert with her fiery glass-blowing husband. "A Lamia in the Cévennes" brings in Keats in an unexpected way (and sent me back to read a poem I haven't looked at for many years) when a painter finds an unexpected sea-serpent in his swimming-pool. And there are some lovely miniatures, as well, especially the Velasquez story "Christ in the House of Jesus and Mary" and "Jael", where a very English film-director looks back on an incident in her early schooldays.

The biographer's tale would be a full-scale novel from anyone else, but by Byatt standards it feels more like an extended novella, with a first-person narrator and only a single plot line. It's great fun, in any case, obviously meant as a slightly tongue-in-cheek penance for the bad press she gave biographers and biography in Possession.

Postgraduate student Phineas G Nanson (*) decides in the middle of a dull seminar that what he cares for are solid facts, and that he doesn't want to become a post-structuralist critic after all. Captivated by an old-fashioned three volume biography of a Victorian polymath, he decides to switch his research topic to the author of the biography, Scholes Destry-Scholes. But this isn't as straightforward as he imagined: Scholes Destry-Scholes turns out to be a very elusive figure, whose traces in the world are teasing, fragmentary and contradictory in a way that he would be forced to call postmodern if he didn't know better. The trail leads him to Carl Linnaeus, Francis Galton and Henrik Ibsen, as well as to the Swedish bee-taxonomist and part-time earth-goddess, Fulla, to Scholes Destry-Scholes's lovely niece Vera, and to a possibly-dubious travel agency called "Puck's Girdle". It's all very confusing, but oddly satisfying, and full of delightfully miscellaneous information about literature, biology and the way they relate — always a core topic for Byatt.

---

(*) Byatt only gives away how she arrived at this rather cryptographic name to those who read the acknowledgements section attentively!

16rocketjk

>11 thorold: "a lot of the more literary accounts are by people who didn't see any front-line service"

I highly recommend Another Hill, an "autobiographical" novel by Milton Wolff, who was the last commander of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Wolff lived into his 90s. Here's a good article about him from the SF Chronicle, published when Wolff died in 2008:

https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Milton-Wolff-fought-fascists-in-Spain-323...

I highly recommend Another Hill, an "autobiographical" novel by Milton Wolff, who was the last commander of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Wolff lived into his 90s. Here's a good article about him from the SF Chronicle, published when Wolff died in 2008:

https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Milton-Wolff-fought-fascists-in-Spain-323...

17thorold

>16 rocketjk: Thanks, sounds interesting. Wolff seems to have taken over more or less at the point where Nelson got wounded and ends his account.

18thorold

>15 thorold: Just for fun, Keats's description of the Lamia in her serpent form. Possibly the first psychedelic snake in English literature:

She was a gordian shape of dazzling hue,

Vermilion-spotted, golden, green, and blue;

Striped like a zebra, freckled like a pard,

Eyed like a peacock, and all crimson barr'd;

And full of silver moons, that, as she breathed,

Dissolv'd, or brighter shone, or interwreathed

Their lustres with the gloomier tapestries—

So rainbow-sided, touch'd with miseries,

She seem'd, at once, some penanced lady elf,

Some demon's mistress, or the demon's self.

Upon her crest she wore a wannish fire

Sprinkled with stars, like Ariadne's tiar:

Her head was serpent, but ah, bitter-sweet!

She had a woman's mouth with all its pearls complete:

And for her eyes: what could such eyes do there

But weep, and weep, that they were born so fair?

As Proserpine still weeps for her Sicilian air.

19thorold

This turns out to be the ninth-oldest book on the TBR shelf, brought back in 2013 from a holiday in Norfolk (probably from the secondhand bookshop at a National Trust property, I would guess) — interesting to see that it's also got a stamp in the back from the Student Union secondhand bookshop at UEA, dated 1996. They sold it for 25p, seven years later I paid a pound!

I've read two other Rose Macaulay books — her last, most famous, work The towers of Trebizond, and her 1920 satire Potterism.

They were defeated (1932) by Rose Macaulay (UK, 1881-1958)

Set in Devon and Cambridge in 1640-1641, on the eve of the English Civil War, packed with poets, politics, and theological disputes, intensely language-based, with a subversive feminist agenda and scarcely a description of a costume or a piece of furniture anywhere in the book, this ought to be my sort of historical novel. And it very nearly was. I loved Macaulay's very precise ear for the patterns of 17th century English — both standard and in various shades of Devon dialect — and her ruthless elimination of 20th century language. Few historical novelists can keep that up so consistently for the length of a whole book. The central characters were promising too: two teenage girls, one a tomboy and the other a scholar; an eccentric sceptical physician; and the poet and clergyman Robert Herrick.

The trouble is, these people look as though they are being set up for an adventure story, but in fact they are only there to allow the author to comment on the ideas of 17th century England. They don't develop in the course of the story, despite listening — ad nauseam — to all sorts of clever people telling each other things they already know about current events. Not much happens, except on the news, and the characters continue much as they were, until the author gets tired of them and eliminates them arbitrarily.

With hindsight, some of what Macaulay is saying about 17th century England, with moderate Anglicans caught between the hardcore puritans on one side and papists on the other on the verge of a destructive conflict, must read onto the fascism and communism of thirties Europe. But a lot of it probably reflects her own somewhat complicated religious feelings as well.

A very interesting book, as history, and a very clever one technically, but I found it a disappointment as a novel. Obviously written as a by-product of Macaulay's Milton biography.

---

I posted about some of the unfamiliar words Macaulay uses here: https://www.librarything.com/topic/325163#7282884

I've read two other Rose Macaulay books — her last, most famous, work The towers of Trebizond, and her 1920 satire Potterism.

They were defeated (1932) by Rose Macaulay (UK, 1881-1958)

Set in Devon and Cambridge in 1640-1641, on the eve of the English Civil War, packed with poets, politics, and theological disputes, intensely language-based, with a subversive feminist agenda and scarcely a description of a costume or a piece of furniture anywhere in the book, this ought to be my sort of historical novel. And it very nearly was. I loved Macaulay's very precise ear for the patterns of 17th century English — both standard and in various shades of Devon dialect — and her ruthless elimination of 20th century language. Few historical novelists can keep that up so consistently for the length of a whole book. The central characters were promising too: two teenage girls, one a tomboy and the other a scholar; an eccentric sceptical physician; and the poet and clergyman Robert Herrick.

The trouble is, these people look as though they are being set up for an adventure story, but in fact they are only there to allow the author to comment on the ideas of 17th century England. They don't develop in the course of the story, despite listening — ad nauseam — to all sorts of clever people telling each other things they already know about current events. Not much happens, except on the news, and the characters continue much as they were, until the author gets tired of them and eliminates them arbitrarily.

With hindsight, some of what Macaulay is saying about 17th century England, with moderate Anglicans caught between the hardcore puritans on one side and papists on the other on the verge of a destructive conflict, must read onto the fascism and communism of thirties Europe. But a lot of it probably reflects her own somewhat complicated religious feelings as well.

A very interesting book, as history, and a very clever one technically, but I found it a disappointment as a novel. Obviously written as a by-product of Macaulay's Milton biography.

---

I posted about some of the unfamiliar words Macaulay uses here: https://www.librarything.com/topic/325163#7282884

20thorold

This one has only been on the TBR for about 18 months, but it's been sitting half-read for several weeks, so I thought it was time to finish it! I bought it after reading Inez and feeling I wanted to read something more Mexican by Fuentes. This is his most famous book, as Mexican as it gets:

La muerte de Artemio Cruz (1962; The death of Artemio Cruz) by Carlos Fuentes (Mexico, 1928-2012)

Cruzamos el río a caballo.

The 71-year-old Artemio Cruz is on his deathbed: we look back at his life through a series of flashbacks, in some kind of arbitrary non-chronological order (and ending with the moment of his birth), each preceded by a stream-of-consciousness reflection by the old man in the sick-room, vaguely aware of what is going on around him but unable to communicate with his family and staff.

Cruz started as a minor player in the Mexican Revolution, a junior army officer from the back of beyond. By the end of his life, he has risen by a mixture of betrayal, corruption and a talent for survival to control a business empire, several key newspapers, and most of the Mexican government. Fuentes uses his career as a foundation for reflecting on the nature of revolutions in general and the Mexican one in particular, the way they are started by people with real wrongs to right on behalf of their communities, but somehow always end up being taken over by people with clear personal ambition and the will to power. He points out what he sees as weaknesses in the structure of postcolonial Mexican society that make it particularly susceptible to being exploited by people like Cruz.

But this is also an extended meditation on mortality, the way our lives seem to centre on outliving other people, but death always turns up sooner or later (Fuentes was only in his forties when he wrote this!). And it's a love-song to Mexico's landscape, culture, ethnic diversity and languages — at the very centre of the text is a long prose-poem celebrating the "Mexican verb" chingar (also the subject of a famous essay by Octavio Paz).

Like most "new novels" of the period, it's not an easy read, and it's often deliberately confusing, mixing very precisely timed and dated sections with passages where we are unsure where or when we are or who is talking. But there's a lot of very exciting, captivating language there, and it's obviously a book that will repay reading two or three times.

---

I don't usually like books with bullet-holes in the covers, but in this case it seems to make sense!

La muerte de Artemio Cruz (1962; The death of Artemio Cruz) by Carlos Fuentes (Mexico, 1928-2012)

Cruzamos el río a caballo.

The 71-year-old Artemio Cruz is on his deathbed: we look back at his life through a series of flashbacks, in some kind of arbitrary non-chronological order (and ending with the moment of his birth), each preceded by a stream-of-consciousness reflection by the old man in the sick-room, vaguely aware of what is going on around him but unable to communicate with his family and staff.

Cruz started as a minor player in the Mexican Revolution, a junior army officer from the back of beyond. By the end of his life, he has risen by a mixture of betrayal, corruption and a talent for survival to control a business empire, several key newspapers, and most of the Mexican government. Fuentes uses his career as a foundation for reflecting on the nature of revolutions in general and the Mexican one in particular, the way they are started by people with real wrongs to right on behalf of their communities, but somehow always end up being taken over by people with clear personal ambition and the will to power. He points out what he sees as weaknesses in the structure of postcolonial Mexican society that make it particularly susceptible to being exploited by people like Cruz.

But this is also an extended meditation on mortality, the way our lives seem to centre on outliving other people, but death always turns up sooner or later (Fuentes was only in his forties when he wrote this!). And it's a love-song to Mexico's landscape, culture, ethnic diversity and languages — at the very centre of the text is a long prose-poem celebrating the "Mexican verb" chingar (also the subject of a famous essay by Octavio Paz).

Like most "new novels" of the period, it's not an easy read, and it's often deliberately confusing, mixing very precisely timed and dated sections with passages where we are unsure where or when we are or who is talking. But there's a lot of very exciting, captivating language there, and it's obviously a book that will repay reading two or three times.

---

I don't usually like books with bullet-holes in the covers, but in this case it seems to make sense!

21thorold

...and if it's Sunday, it must be time for another Schiller play (not for much longer, though: only one-and-a-half to go after this one). And a slightly poignant subject, as it reminds me that, were it not for COVID, I'd have been off to Sicily next week. No multi-media this time — the operatic versions are all pretty obscure and none has lasted in the repertoire — but I did listen to Schumann's overture for the play, of course.

Die Braut von Messina oder Die feindlichen Brüder: ein Trauerspiel mit Chören (1803; The bride of Messina) by Friedrich Schiller (Germany, 1759-1805)

Written in the winter of 1802-1803 and first performed in Weimar in February 1803, this is a largely experimental work, and one of those cases where the experiment seems to demonstrate quite clearly that the hypothesis it was based on is invalid. The play comes with an essay in which Schiller deprecates the tendency for naturalism in drama and justifies reviving the Greek idea of a Chorus as a way of making drama more abstract and stylised, better able to achieve poetic authenticity because it isn't tied to the mechanical (and artificial) business of imitating real life on a stage.

The play is a simple story, stripped to the bare bones of narrative, and with only five speaking parts plus chorus. Unlike Schiller's other late plays, it isn't tied to a historical subject: the choice of Messina for the setting is simply a dodge to allow Schiller to mix ancient Greek and Christian motifs. Like The Robbers, it's about rivalry between brothers. Queen Isabella, who clearly isn't trained in narratology, has sent her infant daughter off to be hidden in a convent, in an attempt to circumvent a prophecy that the girl would be responsible for the deaths of her brothers. Now everyone is grown up, and both the brothers, independently, have fallen desperately in love after a chance meeting with an unknown young girl in a remote convent. We don't need telling how this is going to end!

Schiller doesn't quite stick to his theoretical principle of making the chorus stand outside the narrative and comment on the action: they are treated more like an opera chorus, split into two groups representing the armed followers of the two rival princes, and they do get hands-on with the action from time to time. In fact, in a lot of ways this play resembles the libretto of a Wagner opera. Wagner clearly took a lot of his ideas about the use of the chorus directly from Schiller, but with about 900% more alliteration in the verse.

Interesting, but I don't think the story is a good match to the format. The characters somehow come over more like stylised soap-opera figures than as the modern versions of Oedipus and Jocasta they are meant to be.

----

Coming soon: https://www.classicfm.com/composers/rossini/william-tell-overture-train-set-and-...

Die Braut von Messina oder Die feindlichen Brüder: ein Trauerspiel mit Chören (1803; The bride of Messina) by Friedrich Schiller (Germany, 1759-1805)

Written in the winter of 1802-1803 and first performed in Weimar in February 1803, this is a largely experimental work, and one of those cases where the experiment seems to demonstrate quite clearly that the hypothesis it was based on is invalid. The play comes with an essay in which Schiller deprecates the tendency for naturalism in drama and justifies reviving the Greek idea of a Chorus as a way of making drama more abstract and stylised, better able to achieve poetic authenticity because it isn't tied to the mechanical (and artificial) business of imitating real life on a stage.

The play is a simple story, stripped to the bare bones of narrative, and with only five speaking parts plus chorus. Unlike Schiller's other late plays, it isn't tied to a historical subject: the choice of Messina for the setting is simply a dodge to allow Schiller to mix ancient Greek and Christian motifs. Like The Robbers, it's about rivalry between brothers. Queen Isabella, who clearly isn't trained in narratology, has sent her infant daughter off to be hidden in a convent, in an attempt to circumvent a prophecy that the girl would be responsible for the deaths of her brothers. Now everyone is grown up, and both the brothers, independently, have fallen desperately in love after a chance meeting with an unknown young girl in a remote convent. We don't need telling how this is going to end!

Schiller doesn't quite stick to his theoretical principle of making the chorus stand outside the narrative and comment on the action: they are treated more like an opera chorus, split into two groups representing the armed followers of the two rival princes, and they do get hands-on with the action from time to time. In fact, in a lot of ways this play resembles the libretto of a Wagner opera. Wagner clearly took a lot of his ideas about the use of the chorus directly from Schiller, but with about 900% more alliteration in the verse.

Interesting, but I don't think the story is a good match to the format. The characters somehow come over more like stylised soap-opera figures than as the modern versions of Oedipus and Jocasta they are meant to be.

----

Coming soon: https://www.classicfm.com/composers/rossini/william-tell-overture-train-set-and-...

22thorold

I got out of the audiobook habit a bit over the summer — mostly from reluctance to get involved in the inevitable tangles between headphones, face-mask and glasses — and forgot that I had this one hanging around about 2/3 listened-to. Time to finish it!

Swimming in the dark (2020) by Tomasz Jędrowski (Poland, Germany, etc. 1985- ) audiobook read by Will M Watt

Well, this is a strange thing! It calls itself a historical novel, and technically that's what it is, since it's set before the author's birth in a time and place he didn't experience himself, and it's also separated from the setting by being written in English but set in a Polish-speaking environment. But apart from that, it's written without any 21st century hindsight that I could spot, as a kind of simple pastiche of an eighties gay novel. Even the style feels like a fairly accurate impersonation of an immature writer of the eighties who has recently been on an American creative writing course and has read far too much James Baldwin, Edmund White and Andrew Holleran. (None of which, as far as I'm aware, is true of the real Jędrowski.)

You could say this fills a gap, in that there aren't all that many first-hand accounts of growing up gay in communist-era Eastern Europe, so maybe a book like this could help us to imagine what that might have been like. But it turns out that what Jędrowski imagines it might have been like is almost exactly the way we would have imagined it too, i.e. Giovanni's room with extra sugar-beet and pierogi, and there is very little in the way of unexpected detail to take us into the specific experience of LGBT life behind the iron curtain.

A charming, sad, love story, if you don't mind things that are a little bit overwritten, but otherwise a somewhat unnecessary book.

Swimming in the dark (2020) by Tomasz Jędrowski (Poland, Germany, etc. 1985- ) audiobook read by Will M Watt

Well, this is a strange thing! It calls itself a historical novel, and technically that's what it is, since it's set before the author's birth in a time and place he didn't experience himself, and it's also separated from the setting by being written in English but set in a Polish-speaking environment. But apart from that, it's written without any 21st century hindsight that I could spot, as a kind of simple pastiche of an eighties gay novel. Even the style feels like a fairly accurate impersonation of an immature writer of the eighties who has recently been on an American creative writing course and has read far too much James Baldwin, Edmund White and Andrew Holleran. (None of which, as far as I'm aware, is true of the real Jędrowski.)

You could say this fills a gap, in that there aren't all that many first-hand accounts of growing up gay in communist-era Eastern Europe, so maybe a book like this could help us to imagine what that might have been like. But it turns out that what Jędrowski imagines it might have been like is almost exactly the way we would have imagined it too, i.e. Giovanni's room with extra sugar-beet and pierogi, and there is very little in the way of unexpected detail to take us into the specific experience of LGBT life behind the iron curtain.

A charming, sad, love story, if you don't mind things that are a little bit overwritten, but otherwise a somewhat unnecessary book.

23thorold

Back to A S Byatt and Frederica:

A whistling woman (2002) by A S Byatt (UK, 1936- )

The fourth of the Frederica novels brings us to 1968-1969, and into a whole series of parallel discussions and debates that were going on in biology, psychology, theology, computer science, linguistics, sociology and philosophy (...at least!) about what we mean by concepts like "mind" and "consciousness" and human identity. Frederica is at one of the focal points of this, in her new role as host of an Ideas programme on the Box; Vice-Chancellor Wijnnobel and his new University are at another, in a weird pairing with the radicals and hippies who have set up an Anti-University in a nearby field; and a third, most intense focus for all this intellectual energy is formed by a Manichaean religious cult that has grown out of the harmless Quaker-led forum, the Spirit's Tigers, which we met in the last book.

The irony, as Frederica notes, is that contrary to everything Dr Leavis taught her, the one thing that doesn't seem to be playing any important role at all in all this scientific-philosophical-religious upheaval is English literature. D H Lawrence is out, Freud and Jung and Chomsky are in. Frederica's own book, Laminations, has aroused interest only among literary journalists (who like having the photo of a TV celebrity to put over their columns), whilst Agatha's Tolkienesque fantasy story Flight North has been ignored by reviewers but turns into a phenomenal word-of-mouth success.

There's a huge amount to take in here, and it's thrown at us so fast that it's easy to get lost. There is still plenty of comedy along the way, but it's offset by our awareness that there are some very bad things going on, and vulnerable people are obviously going to get hurt, especially in the cult and among the student rebels. So it's not as much fun to read as Babel Tower, but still very worthwhile.

---

A pity about the Vintage cover: they used what should have been a very interesting early colour photograph by John Cimon Warburg ("The Dryad", ca. 1910), but somehow made it look like generic, meaningless airbrush art. The peacock covers on some other editions are much better.

Vintage even violates the first law of modern cover design by failing to put the text label where it will obscure the model's face...

A whistling woman (2002) by A S Byatt (UK, 1936- )

The fourth of the Frederica novels brings us to 1968-1969, and into a whole series of parallel discussions and debates that were going on in biology, psychology, theology, computer science, linguistics, sociology and philosophy (...at least!) about what we mean by concepts like "mind" and "consciousness" and human identity. Frederica is at one of the focal points of this, in her new role as host of an Ideas programme on the Box; Vice-Chancellor Wijnnobel and his new University are at another, in a weird pairing with the radicals and hippies who have set up an Anti-University in a nearby field; and a third, most intense focus for all this intellectual energy is formed by a Manichaean religious cult that has grown out of the harmless Quaker-led forum, the Spirit's Tigers, which we met in the last book.

The irony, as Frederica notes, is that contrary to everything Dr Leavis taught her, the one thing that doesn't seem to be playing any important role at all in all this scientific-philosophical-religious upheaval is English literature. D H Lawrence is out, Freud and Jung and Chomsky are in. Frederica's own book, Laminations, has aroused interest only among literary journalists (who like having the photo of a TV celebrity to put over their columns), whilst Agatha's Tolkienesque fantasy story Flight North has been ignored by reviewers but turns into a phenomenal word-of-mouth success.

There's a huge amount to take in here, and it's thrown at us so fast that it's easy to get lost. There is still plenty of comedy along the way, but it's offset by our awareness that there are some very bad things going on, and vulnerable people are obviously going to get hurt, especially in the cult and among the student rebels. So it's not as much fun to read as Babel Tower, but still very worthwhile.

---

A pity about the Vintage cover: they used what should have been a very interesting early colour photograph by John Cimon Warburg ("The Dryad", ca. 1910), but somehow made it look like generic, meaningless airbrush art. The peacock covers on some other editions are much better.

Vintage even violates the first law of modern cover design by failing to put the text label where it will obscure the model's face...

24thorold

A quick in-between read, to make a bit of space on the TBR — books from my last little encounter with ABE Books are starting to roll in. This is one I bought in August after baswood wrote about it in his thread. I hadn't heard of Shirley Jackson, perhaps because she's more known in the horror genre, but evidently I should have!

As Bas pointed out, this came out the same year as Catcher in the rye; it fits in with all those post-war adolescent rebel books (Nada, Bonjour tristesse, De avonden, etc.) — although Jackson was at least a generation older than most of those writers — and it also fits in nicely with a few "clever-young-woman-at-college" books I've been reading lately, like The bell-jar and The shadow of the sun. I've still got Dusty Answer on my shelf as well.

Hangsaman (1951) by Shirley Jackson (USA, 1916-1965)

This looks superficially like a standard teenage coming-of-age novel: 17-year-old Natalie goes off to college as the first step on her quest to become a writer and an autonomous human being, rather than a mere extension of her parents. The other girls are there for purely social reasons and don't like her, but she eventually hooks up with a couple of other outcasts: a bored young faculty-wife who drinks too much, and the rebellious Girl Tony, who flits in and out of other people's rooms in the dark and helps herself to what she needs.

But Jackson evidently doesn't like formulas: the book is determinedly eccentric in all kinds of ways. It's written in the third person, in a precise, elegant, but slightly mad literary style — rather as George Eliot might write after her third Martini. And where every coming-of-age novel pivots on a moment of sexual self-discovery, this novel is made to pivot on two "Malabar Caves"-type moments of we-don't-know-what. Natalie goes into the woods with a man in her parents garden, and she goes into the woods with Girl Tony near the abandoned amusement park. On neither occasion are we told what — if anything — happened, but she comes out a different person both times. Indeed, we're never quite allowed to be sure that Girl Tony exists outside Natalie's own mind.

Natalie is entirely clear-sighted about the subtle mismatches in the world around her: everyone is busy telling clever girls how much potential they have and what wonderful opportunities there are in front of them, but as far as the eye can see the only role-models are clever girls who have run into the sand, married too young to faculty members (or to Natalie's father) and living out their stupefyingly boring days in an alcoholic haze, serving cocktails at parties where their husbands flirt with the next generation of clever girls. The men are allowed to carry on in their Mr Bennet delusion that the world exists purely for their own entertainment, and never for a moment notice that they are tyrannising the families they love so dearly.

But then there are also mismatches in Natalie's own mind. Does she actually have any solid reason to suppose that she is Natalie Wade, she asks herself whenever she has to tell someone her name. Couldn't she just as well be someone else, or no-one at all?

A clever, witty, slightly puzzling book, beautifully written by someone who obviously knew exactly what she was doing with her typewriter at all times, and had a very clear ear for other people's language.

---

Not sure what Penguin are doing with these covers: the new design with the narrow white strips top and bottom just makes it look as though they can't afford to print all the way to the edge of the page. The photograph by Anka Zhuravleva is nice enough, if somewhat generic, but it's been spoilt by brutally cropping it down the middle of the face for no obvious reason.

As Bas pointed out, this came out the same year as Catcher in the rye; it fits in with all those post-war adolescent rebel books (Nada, Bonjour tristesse, De avonden, etc.) — although Jackson was at least a generation older than most of those writers — and it also fits in nicely with a few "clever-young-woman-at-college" books I've been reading lately, like The bell-jar and The shadow of the sun. I've still got Dusty Answer on my shelf as well.

Hangsaman (1951) by Shirley Jackson (USA, 1916-1965)

This looks superficially like a standard teenage coming-of-age novel: 17-year-old Natalie goes off to college as the first step on her quest to become a writer and an autonomous human being, rather than a mere extension of her parents. The other girls are there for purely social reasons and don't like her, but she eventually hooks up with a couple of other outcasts: a bored young faculty-wife who drinks too much, and the rebellious Girl Tony, who flits in and out of other people's rooms in the dark and helps herself to what she needs.

But Jackson evidently doesn't like formulas: the book is determinedly eccentric in all kinds of ways. It's written in the third person, in a precise, elegant, but slightly mad literary style — rather as George Eliot might write after her third Martini. And where every coming-of-age novel pivots on a moment of sexual self-discovery, this novel is made to pivot on two "Malabar Caves"-type moments of we-don't-know-what. Natalie goes into the woods with a man in her parents garden, and she goes into the woods with Girl Tony near the abandoned amusement park. On neither occasion are we told what — if anything — happened, but she comes out a different person both times. Indeed, we're never quite allowed to be sure that Girl Tony exists outside Natalie's own mind.